I have spent my career studying water, how it moves, how it sustains ecosystems, and how it supports human life. But the longer I work in this field, the more uneasy I become about a simple question most people never think to ask: Is this water actually safe?

Not safe according to a regulation. Not safe according to a decades-old testing code. But safe in the way that truly matters, safe for human contact, safe for long-term health, safe for the communities that depend on it. Because what I am seeing, in system after system, is that the way we measure water contamination, and the health risks tied to human contact, is simply not good enough.

When most people think about water safety, they think about drinking water. That is important, of course. But human exposure goes far beyond what we drink. We swim in rivers, boat in reservoirs, fish in lakes, and let our children and pets play in coastal waters. Every one of those interactions carries potential health risks.

Yet the systems we rely on to assess those risks are built on narrow indicators, most commonly fecal indicator bacteria such as E. coli and coliforms. These organisms serve as proxies, signaling the possible presence of sewage contamination. If counts exceed a regulatory threshold, a water body may be deemed unsafe.

But here is the problem: these indicators do not tell the full story. As discussed in my published work on watershed contamination pathways and water quality assessment, traditional indicators often fail to identify the source of contamination or the true pathogen load affecting human health. Indicator bacteria may persist in sediments, multiply outside host organisms, or fluctuate dramatically depending on hydrological conditions.

I can test the same site days apart or even hours apart and get dramatically different readings. Does that mean the health risk disappeared? Or that we simply failed to capture it? Too often, policy decisions rest on these incomplete snapshots.

In my field research on microbial contamination and watershed systems, I have documented persistent exceedances of regulatory thresholds across multiple sites. In some monitored systems, violation rates were consistent, yet the broader regulatory framework remained unchanged. Compliance becomes a technical exercise rather than a meaningful measure of public safety.

This gap between conventional indicator monitoring and advanced source tracking techniques is not academic; it is consequential.

In recent studies applying microbial source tracking and refined analytical methods, we have been able to distinguish human-derived contamination from other environmental sources, identifying sewage infiltration pathways that would not have been detected using standard regulatory tests. These approaches provide greater specificity, allowing us to trace contamination to failing septic systems, infrastructure leaks, or direct discharge.

Under conventional monitoring, those risks would have remained obscured. Waterborne pathogens contribute to gastrointestinal illness, dermatological infections, and respiratory conditions. My broader work in water science and quality assessment has also emphasized the need to connect ecological health with human health exposure risk. Environmental degradation is not isolated from public health; it is a continuum.

Part of the challenge lies in human psychology. There is a deep cultural trust in water systems, particularly in developed nations. We associate contamination crises with distant geographies, not our own communities. When I present findings that indicate sewage contamination in U.S. reservoirs, the response is often disbelief.

But infrastructure tells the story. Much of our municipal water and sewage piping is decades, sometimes more than a century old. Systems designed for smaller populations now serve sprawling metropolitan regions. Leakage, overflow events, and stormwater surges introduce contaminants into waterways with alarming regularity.

Private septic systems are no different; in fact, they pose a more localized risk. They are in our homes, they are in our communities, and they are in our schools. In multiple field investigations, I have documented structural failures and leaching patterns that contribute to diffuse contamination of adjacent water bodies. These failures are often invisible until contamination is advanced.

We have built vast networks to move water efficiently. But we have not invested equally in ensuring its safety after use. And then there is the economic reality. Advanced testing, microbial source tracking, pathogen assays, and genomic analysis are more expensive than routine indicator monitoring. Municipalities and regulatory agencies often default to lower-cost testing because it satisfies statutory requirements.

But compliance is not the same as protection. If a water body meets outdated regulatory thresholds yet still exposes the public to pathogens, have we truly safeguarded health? Or have we merely met the minimum legal requirement?

This is where policy must evolve alongside science. We must rethink how we define ‘safe.’ We must expand monitoring frameworks to include contamination source identification, exposure pathways, and cumulative health risk assessment. We must modernize infrastructure, not only treatment plants but also distribution systems and sewage networks.

Yes, these reforms are costly. But we must ask the harder question: What is the cost of inaction?

Healthcare burdens linked to waterborne disease. Lost productivity. Environmental degradation. Long-term chronic exposure risks. Preventive environmental management is almost always more cost-effective than reactive healthcare intervention. Public health systems already strain under avoidable disease loads. Water and sanitation, if treated with the seriousness it deserves, could reduce that burden substantially.

Yet we remain reactive rather than proactive. We wait for visible crises, a spill, an outbreak, a closure, before acting. Routine contamination, diffuse pollution, and systemic leakage rarely generate urgency. They are chronic problems, and chronic problems are easier to ignore. Until they are not.

I often return to the same concern: we are operating with analytical tools that were never designed to answer the full scope of today’s risk landscape. Indicator organisms were a starting point, not an endpoint. Science has advanced. Our policies have not kept pace.

If we continue relying on incomplete measures, we will continue underestimating exposure, underreporting contamination, and underprotecting the public. Water is fundamental to life. It is finite, recycled, and shared across ecosystems and communities. When we contaminate it, we contaminate our own survival systems. So I return to the question that has troubled me throughout my career: Is this water actually safe?

If the only answer we can offer is that it meets a regulatory number, without deeper analysis, without source identification, without exposure modeling, then we are placing trust in a system that has not earned it.

And the true cost of that misplaced trust will not be measured in compliance reports. It will be measured in human health.

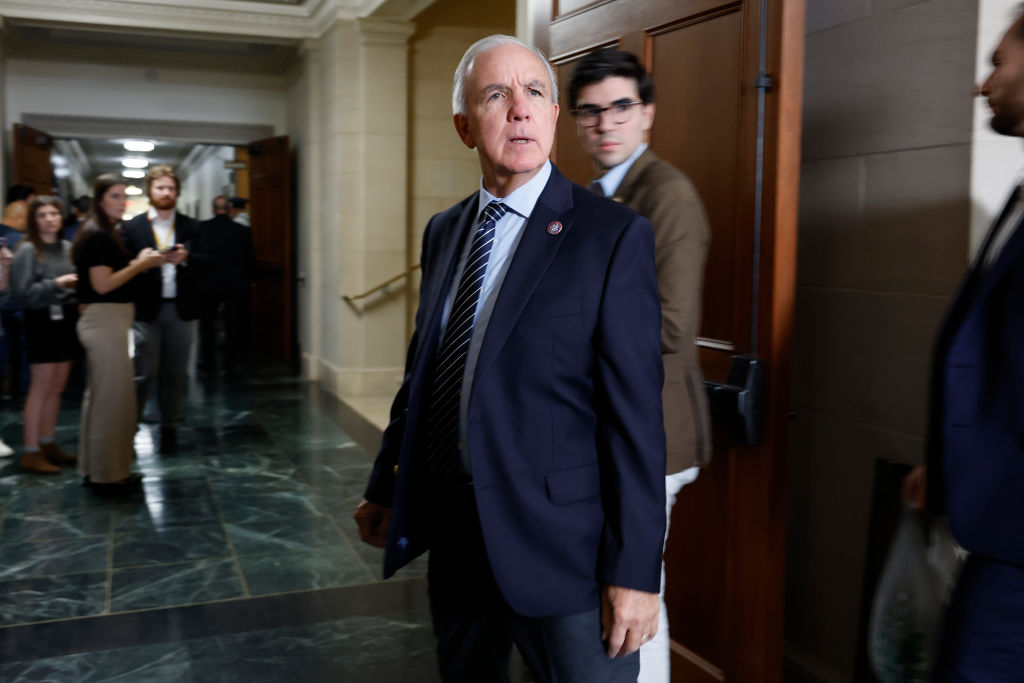

About the Author:

Thomas D. Shahady, Ph.D., is a professor of Environmental Science at the University of Lynchburg and a consultant through the Center for Water Quality. His research focuses on freshwater ecosystems, microbial contamination, and the human health risks associated with water exposure. Over the course of his career, he has led watershed monitoring projects in the United States and internationally, advancing applied research on water quality assessment, infrastructure impacts, and environmental public health.