AFP

After several missiles exploded near his house outside Kyiv, Kyrylo Barashkov decided the only way to keep his family safe was to build his own bunker.

“That’s what we need more than any other thing — more than a good car, more than repairing the house — because it’s safety. If you’re dead, you need nothing (any) more.”

The cost of constructing the shelter was around $20,000, the 43-year-old immigration lawyer says — less than his SUV.

“I can’t say it’s a lot for safety, for a calm brain, a calm heart,” says Barashkov, who lives on a housing estate of low, wooden houses just outside the Ukrainian capital.

The door to the bunker stands on Barashkov’s tree-lined street. His neighbours tend not to talk much, Barashkov says, but he has given them all the code to the shelter.

Refuge from attack is available to everyone who can fit inside the bunker — as many as 15 people.

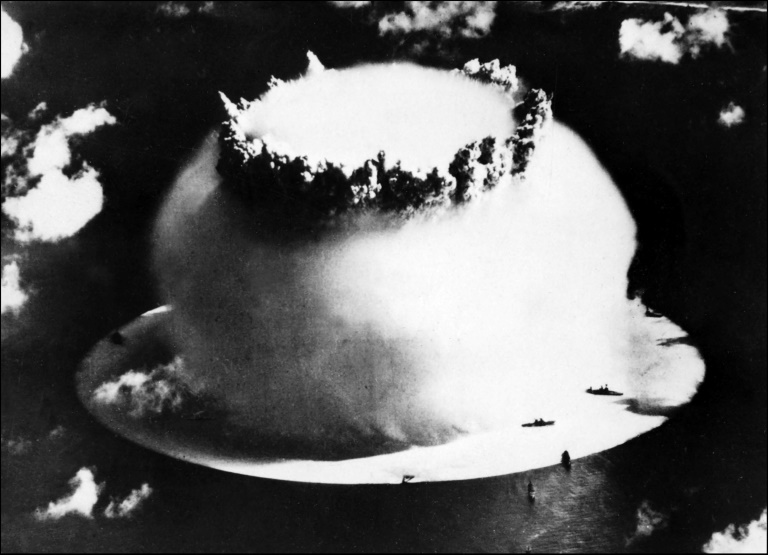

Those around him “feel better every day when they know that any time, they have a bunker nearby, so it will house them in the case of a huge attack, a nuclear attack”, Barashkov says.

Down the 14 steps to the wood-panelled bunker, there are two sofas, a log stove and an as-yet-unused portable toilet — in case of a lengthy stay downstairs.

The longest stint so far has been seven hours, Barashkov says, although he admits he popped up to the surface to smoke a cigarette every so often.

Inside, the facility is kitted out with Wi-Fi and a large power bank to charge mobile phones and other devices. Should the electricity be cut, the bunker is equipped with its own diesel generator to keep the lights on.

The shelter is a good five metres (16 feet) underground, which the owner says is enough to avoid “99 percent” of possible strikes.

“We had a few explosions right here,” Barashkov says, pulling up a video from a blast outside his home in January.

Barashkov says he even comes down to sleep in the bunker, where he finds peace in the dark away from the noise and light pollution at the surface.

His attitude contrasts with that of many Kyiv residents, who have stopped seeking shelter during air raids, tired of nights in crowded metro stations or damp cellars.

While some of his neighbours are regular visitors, others have not yet opted to make use of the shelter.

“To me, it’s strange, to be honest,” he says.

“We should care about children, we should care about women, we should care about ourselves, because we should survive during all this.”

Protecting his family is especially important to Barashkov, whose wife has just given birth to their son.

He was “nervous all the time” when she was pregnant, and they sheltered in the bunker together.

Their son has not yet had to take cover, “thanks to God”, he says.

AFP