AFP

The United States called Tuesday for the release of hundreds of jailed Cubans as the country marked two years since unprecedented protests sparked by deep economic and social problems that have only gotten worse since then.

The streets of the capital Havana were calm under surveillance of the security forces, AFP observed, as government opponents and activists denounced the presence of police outside their homes.

On July 11 and 12, 2021, thousands of Cubans spontaneously took to the streets of dozens of cities and towns with people chanting, “Freedom!” and “We are Hungry.”

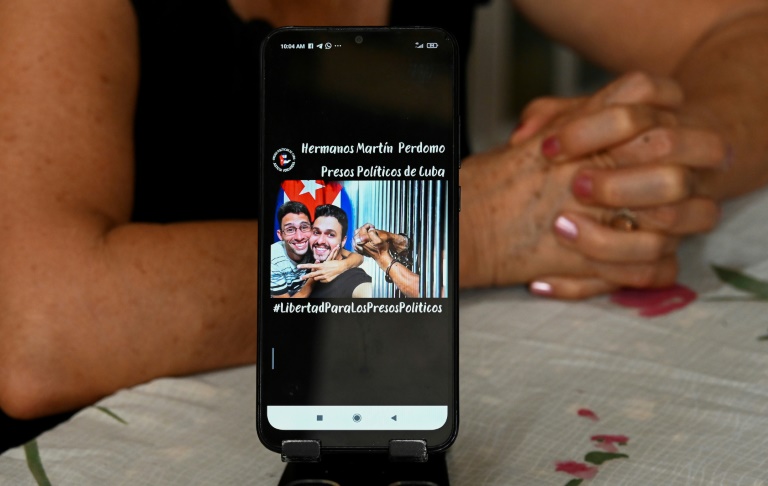

More than 1,500 were arrested in the aftermath, of whom about 700 are still behind bars, according to rights group Justicia11J, which operates from outside the communist island.

Nearly 500 were sentenced to prison terms of up to 25 years, according to the authorities, on charges including “sedition.” Many activists have left the country.

Havana has accused Washington of orchestrating the protests in a bid to overthrow the one-party government.

“The United States has guided, financed and incited acts of violence and provocation against the authorities in Cuba,” deputy foreign minister Carlos Fernandez de Cossio repeated on his Twitter account Tuesday.

For his part, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken called for “the immediate release of unjustly detained political prisoners.”

In a statement, he also urged the international community “to join us in demanding the Cuban government release the hundreds of students, journalists, artists, young people, and others unjustly imprisoned.”

Yoani Sanchez, founder of the news site 14ymedio, said police were deployed Tuesday “on the ground floor of our building in Havana to prevent us from going out on the streets.”

The site is a rare independent voice in a country where newspapers and broadcasters are linked to the ruling Communist Party of Cuba.

Two years after the uprising, Cubans still battle endless queues for food, fuel and medicine, inflation is in the double digits, tourism is battling to recover, and there has been a drop in sugar production — another mainstay of the economy.

A lack of foreign currency and peso devaluation have caused prices to rise and ever more Cubans are seeking to flee the island.

Last year, President Miguel Diaz-Canel promised the country of 11 million people would soon emerge from a “complex” economic situation worsened by six decades of US sanctions and the coronavirus pandemic, which bludgeoned the critical tourism sector.

But another year on, little, if anything, has changed.

“The economic situation is the same as before July 11, or even worse, because there is even less food, less medicine, the prices are very high,” Havana resident Yaneysi, 31, told AFP. She did not want to give her full name.

“The economy has deteriorated a lot lately… we are suffering,” added Ana Maria Hernandez, a 65-year-old accountant.

After almost six decades of near-total state control of the economy, Havana authorized small and medium enterprises in 2021.

This has gone some way toward alleviating shortages of certain products, but widened inequalities because of higher prices out of reach of many who rely heavily on government assistance.

Increasingly fed up with the state of affairs, Cubans have become less hesitant to express their discontent with the authorities.

Last year, there were intermittent demonstrations against power outages in several provinces in a country where political opposition is not allowed and protests prior to 2021 were very rare indeed.

In May this year, dozens of people demonstrated against food and drug shortages in Caimanera, a town some 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) from the capital.

As Cubans have become emboldened, the government has reacted with arrests and harassment, according to activists, and by moving to mute the dissident discourse with intermittent internet blackouts.

According to Justicia11J, the country is dealing with a “new wave of repression.”

In May, Amnesty International said the human rights situation in Cuba “continues to deteriorate,” pointing to a new penal code adopted last year that critics say was designed to preemptively quell any displays of public discontent.

Under the law, a prison term of up to two years can be incurred for demonstrations by one or more people “in breach of provisions.”

The Vatican and European Union have also called for the release of imprisoned demonstrators.

AFP

AFP

AFP