KEY POINTS

- BRI lending to 52 countries hit $102 billion in 2019

- U.S., India, Japan and France have been vocal of their BRI doubts

- Some Chinese nationals have been targeted abroad due to their BRI links

As China prepares to celebrate the 10th year of its signature Belt and Road Initiative, its efforts to expand influence and trade connections are coming under intensified scrutiny. And it may be no coincidence that western nations under the leadership of the United States recently proposed a rival initiative connecting India, a rising global economic star that has refused to join the BRI, with Saudi Arabia and Europe.

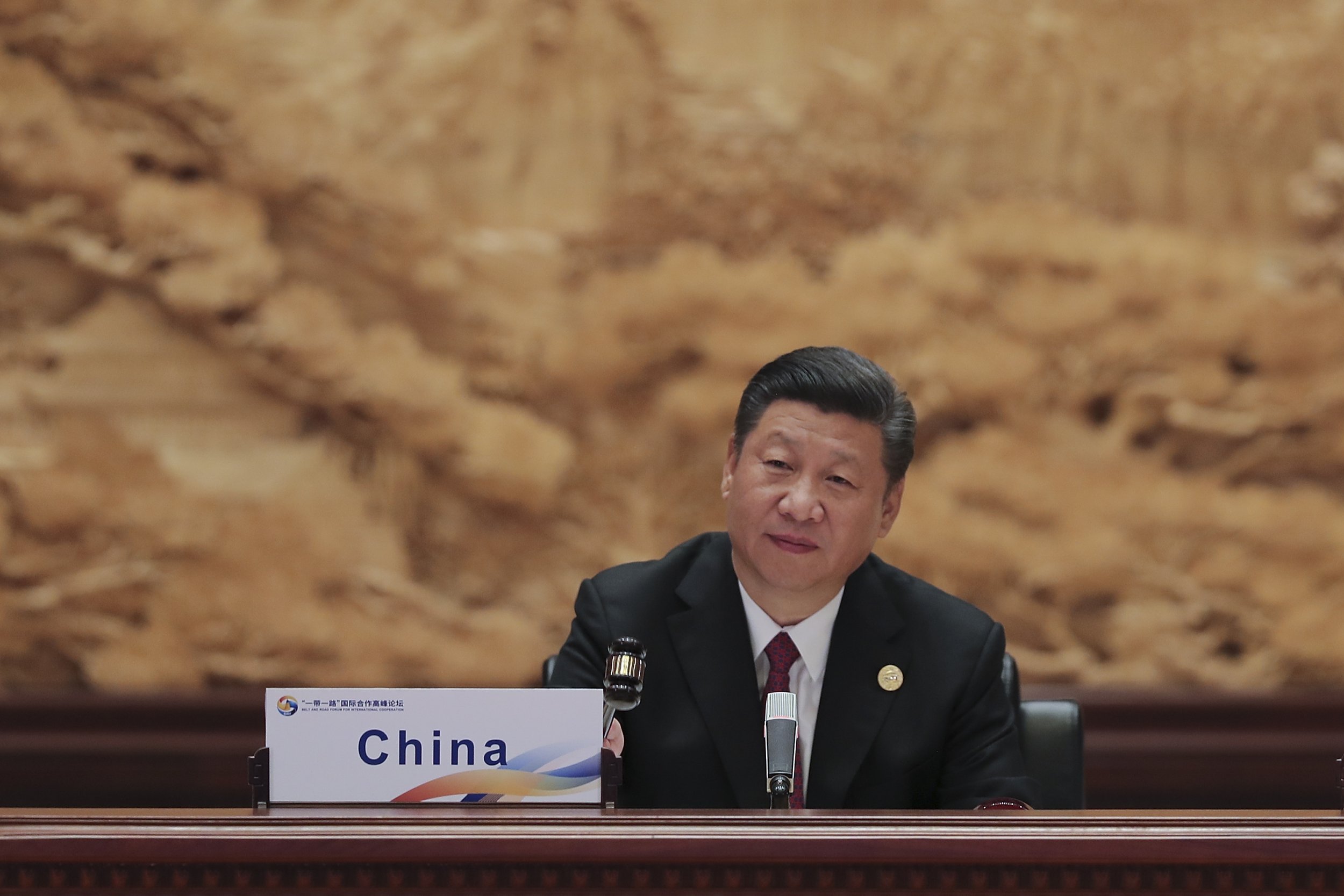

China will host the third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in October, and 90 countries have reportedly confirmed that they are attending. But that comes under the shadow of a big negative headline — Italy has expressed a desire to exit the program, saying it benefited China more than Italy. Plus, the talk of how the project and China’s loans are pushing poorer countries into indebtedness has refused to die down despite Beijing’s best efforts.

What is the BRI?

The BRI is a trans-continental project that includes passage links between China and Southeast Asia, South Asia, central Asia, Russia and Europe by land. It also includes a “21st century Maritime Silk Road,” which is a sea route project that connects China’s coastal regions with Southeast and South Asia, the South Pacific, the Middle East, eastern Africa and Europe.

Inspired by the ancient Silk Road that dates back to the Han dynasty, the BRI has five main priorities: policy coordination, connectivity of facilities, unrestricted trade, integration of financial systems and people-to-people ties.

To finance projects that will establish transnational passages, China lends money to countries that are taking part in the project. As of 2019, China’s total lending to 52 BRI countries had hit $102 billion, nearly reaching the same levels of the World Bank.

How countries have reacted to the BRI

Neighbor India has expressed suspicion of the BRI since it was first launched. The country turned down China’s invitation to the 2017 BRI Forum, and a spokesperson of India’s foreign ministry said the international community was “well aware of India’s position.”

India is particularly opposed to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor project, which has a section that runs through the disputed territory of Kashmir.

Russia, one of Beijing’s friends, has also reportedly been considering dropping out of BRI cooperation since 2017. While the two countries continue to build on trade cooperation, there have been concerns from the Russian Ministry of Transport regarding inadequate financial resources and delays in completing projects.

Japan initially had a dismissive attitude toward the BRI, but has since adopted a “conditional engagement” approach. It has also committed over $300 billion in financing to various infrastructure projects across Asia as it attempts to balance its suspicions of China’s intentions with its own interests of regional infrastructure development.

In the United States, analysts said Washington’s approach to the BRI transitioned “from an initial ambivalence to near total distrust” under the Trump administration. The Biden administration has maintained his predecessors’ skeptical view of the initiative. Still, no U.S. administration since the BRI’s inception has offered a more appealing alternative to world nations.

President Joe Biden did launch the Build Back Better World Initiative (B3W), but there have been concerns that the program’s lack of financing hampers its potential to become a serious challenger to the BRI. The B3W has since been renamed to Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment.

Over in Europe, more than two-thirds of European Union members have formally signed up for the BRI, including Greece and Hungary. But there are also some skeptics, led by France. French President Emmanuel Macron, in particular, has said that the BRI could be Beijing’s way of making BRI signatories “vassal states.”

A development pathway or a debt trap?

The term “debt trap” has come to be repeatedly associated with the BRI in media reports and conversations at multilateral lending fora.

In July, Italy’s Defense Minister Guido Crosetto said his country’s decision to join the initiative was “improvised and atrocious.” Crosetto argued that while Chinese exports to Italy increased significantly, Italian exports to China did not reach the same levels as its counterpart.

And last week, Italian Deputy Prime Minister Antonio Tajani said the “Silk Road did not bring the results we expected.” Italy will evaluate its participation in the initiative and decide whether or not the country should stay in the program, he said. Italy was the first major western country to join the initiative in 2019.

But even before Italy raised its doubts about the program, there have been concerns about the BRI becoming a “debt trap,” especially for developing countries.

A 2018 report by the Center for Global Development found that eight BRI partners — Djibouti, Mongolia, the Maldives, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Laos, Pakistan and Montenegro — were at high risk of “debt distress” due to their participation in the initiative.

Multiple reports have characterized Sri Lanka’s troubles with the Hambantota Port project as a “deb trap” issue. Sri Lanka handed over the port to China in 2017 on a 99-year lease after it struggled to repay its BRI debts.

However, some experts have argued that Sri Lanka’s debt crisis shouldn’t be connected to the Hambantota Port’s lease as Colombo had actively solicited the project and that loans from China account for only a fraction of the country’s overall sovereign debt.

Chinese nationals targeted over BRI links?

Reports of kidnappings among Chinese nationals gained focus in 2021 as the cases were linked to China’s efforts at pushing the BRI in Africa.

In November 2021, five Chinese nationals working on a mine in southeast Democratic Republic of Congo were kidnapped. Earlier last year, armed men kidnapped three Chinese nationals and killed two Nigerian staff working at a power project.

Cullen S. Hendrix, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), wrote that the BRI and China’s Confucius Institute – a culture-centric program – “created a network of vulnerable Chinese nationals abroad.”

Hendrix noted that several BRI projects and Confucius Institutes are located in areas where there is political unrest, such as parts of South and Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. “What makes Chinese targeting unique are the ties many Chinese nationals have to Chinese SOEs (state-owned enterprises) and BRI-financed projects,” he said.

What’s next for the BRI?

China’s BRI ambitions won’t be dampened by issues that have haunted its 10-year run. Experts say Beijing will find areas to improve, as it attempts to move attention away from the problems.

Some experts believe there will be signals of “greening the BRI” as China continues to reiterate its climate-action leadership. Others suggest that in the coming years, China may also opt for a lower debt risk approach to dispel suspicions about its intentions and also encourage more interest in its projects.