As China continues to be under never-ending COVID-19 lockdowns, its President Xi Jinping is traveling all over central Asia. He’s seizing the opportunity to expand Beijing’s influence in the region when Russia’s President Vladimir Putin is too busy fighting a losing war in Ukraine.

The word crisis consists of two characters in Chinese, one that means danger and another that means opportunity. In the Russian-Ukraine war, China has set aside the risks of siding with Russia and grabbing the chance to turn an old adversary into its near vessel state; and advance its Central Asia agenda.

That’s according to Juscelino Colares, a professor of business law and co-director of the Frederick K. Cox International Law Center. He sees Russia as increasingly dependent on China in the aftermath of breaking the Russian-Ukraine war, which has lasted beyond Putin’s expectations.

“Because Putin’s dreamed quick victory and domination of Ukraine have not materialized, and Russia is more dependent on Chinese oil, grain, and fertilizer purchases than ever, China’s Xi Jinping visit to Kazakhstan (and four other Central Asian former Soviet Republics) this week, his first foreign trip since the start of the pandemic, can barely provoke a response from Russia, now nearly a vassal state to China,” he told International Business Times in an email.

But China doesn’t want to commit Europe’s mistake and rely too much on Russia for its energy needs. That’s why President Xi fostered close relations with oil-rich Kazakhstan, during his Central Asia trip, before meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin in Samarkand, Uzbekistan.

Nonetheless, Beijing is trying to appease Russia by describing China’s relations with Kazakhstan as “always hoping to serve as a bridge between China and Russia,” according to Professor Colares, which finds Beijing’s approach quite conspicuous.

Meanwhile, he sees Xi’s Kazakhstan visit serving China’s interests in other ways, in addition to securing alternative oil supplies, like developing multiple channels of rail access to European and Middle Eastern markets, the basis of China’s “Belt and Road” initiative

Then there’s China’s capitalizing on Russia’s military, economic, and political weakening from the lingering war and the protracted Western economic sanctions. They limit Russia’s ability to respond effectively, at least in the current context.

Moreover, Professor Colares thinks that the dire situation Moscow has arrived in could explain why, earlier on, China may have encouraged Putin to invade Ukraine, presumably foreseeing its severe consequences for Russia; and the opportunities it opens for Beijing in central Asia.

“Skeptics should remind us that a regime that embarked on massive genocides against its people (alleged non-communists during the Cultural Revolution) and co-citizens (current Uyghur persecution in Xin Jiang Province) would seem to care little for Ukrainians, whom the Chinese Communist Party perceives as a far distant people,” he said.

Yannis Tsinas, a former Washington military diplomat analyst, goes a little further than that, thinking that the Russian-Ukraine war will end, weakening the EU, too, America’s closest ally. “The war is advancing China’s agenda to defeat the U.S eventually,” he told International Business Times in a telephone interview. “But Beijing is far-far away from achieving this goal.”

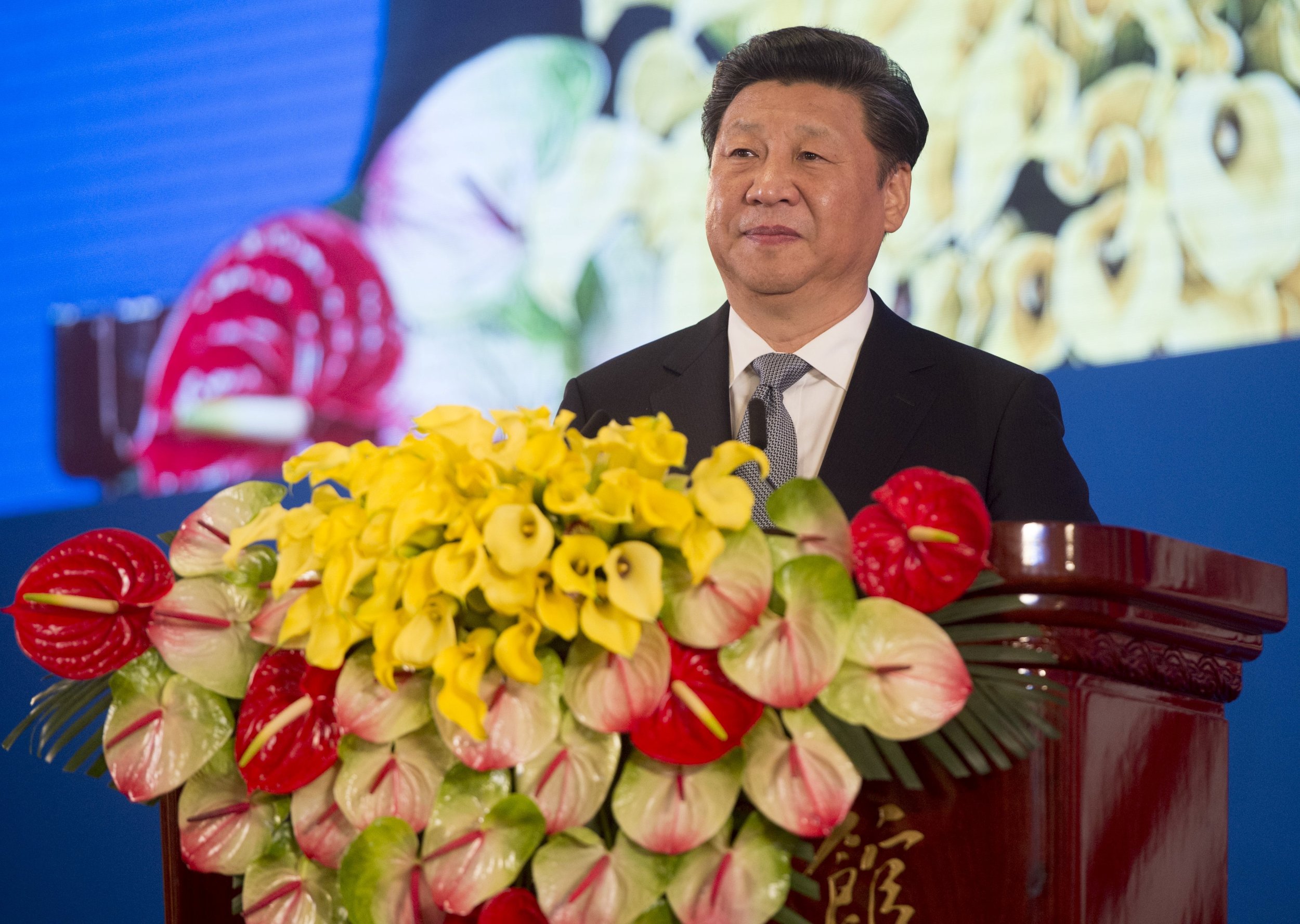

REUTERS / POOL / SAUL LOEB