A Ukrainian pilot project to compensate women raped by invading Russian soldiers could offer a roadmap for dealing with wartime sexual violence, says a Nobel Prize winner and expert on conflict atrocities.

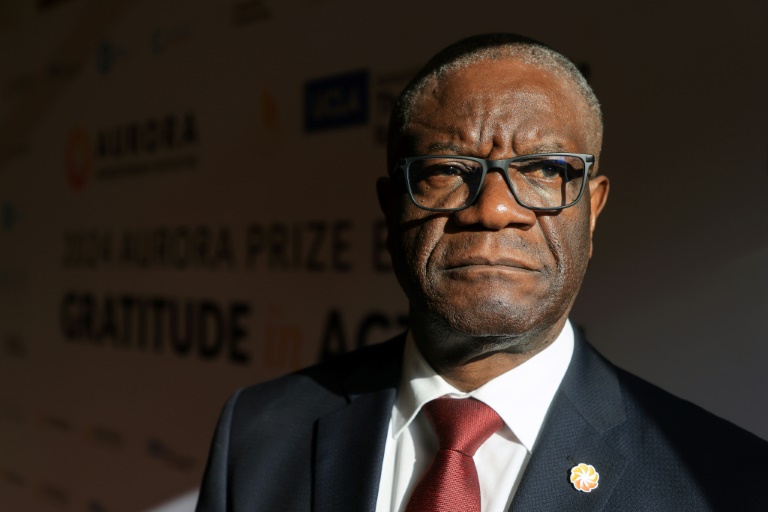

Denis Mukwege, a 69-year-old medical doctor, has dedicated his life to helping victims of some of the most horrific violence committed by military men.

In his native Democratic Republic of Congo, which has been riven by violence for years, he has treated tens of thousands of women raped or mutilated by rampaging militias.

Many victims feel they are invisible, unable to speak out against men who commit their crimes in the knowledge they will likely never be held to account.

Mukwege says perpetrators must be punished, but their victims should not have to wait until their attacker appears in court years — or even decades — later.

“It is absolutely essential to be able to develop reparation programs in countries so that when women are raped and the community has not protected them, the community can at least repair what has been done,” he told AFP in an interview in Los Angeles.

Ukraine is trying to do just that, he said, even as it continues to battle Russian troops who the United Nations says have committed repeated war crimes and human rights violations.

Kyiv is working with the Global Fund for Survivors, an NGO that Mukwege created with Nadia Murad, a victim of sexual violence with whom he shared his 2018 Nobel Peace Prize.

The Ukrainian government is hoping to draw from Russian assets frozen after the country launched its invasion to compensate the victims.

“Ukraine will be the first country in wartime to compensate 500 victims of sexual violence,” Mukwege said.

“Victims cannot wait for the war to end,” he added. “If they are asked to wait until the war is over, many of them may disappear… They may die of illness, of depression. They may die simply of exclusion.”

Mukwege’s life as a gynecologist has been dominated by dealing with the horrific violence wrought on women by men at war.

The DRC has been wracked by violence for decades fueled by civil war and internal conflicts often set off by the scramble for its valuable natural resources.

“When I treated the first victim, I was almost certain that it was a one-time problem and not one that was going to last 25 years,” he told AFP in Los Angeles, where he was this month awarded the Aurora Prize for Awakening Humanity, a $1 million purse for activists and humanitarian workers.

“The war changed everything in my life.”

Mukwege founded the Panzi Hospital in Bukavu, where he and his staff have now treated tens of thousands of women.

He says he can tell where a woman is from by the way she has been brutalized.

“In Bunyakiri, they burn the women’s bottoms. In Fizi-Baraka, they are shot in the genitals. In Shabunda, it’s bayonets,” he told the New York Times in an earlier interview.

The objective of sexual violence, he adds, also varies from conflict to conflict.

In Haiti, Colombia and the DRC, rape has been used for sexual enslavement and trafficking, while in South Sudan it is used for ethnic cleansing, he told AFP.

The Panzi Hospital adopts a holistic approach to treating women, addressing medical, psychological, socioeconomic and legal needs, he says.

The horror of what he deals with is tempered by the courage of those he treats, some of whom use their experience as motivation to help other victims.

The hospital and his work have made him unpopular in some quarters — there has been at least one assassination attempt on him, and when he ran for president of DR Congo, he received fewer than 40,000 votes from a population of more than 100 million people.

Sometimes he feels hopeless about the fight to end wartime sexual violence.

But he knows he will not stop.

New conflicts — like that between Israel and Hamas — bring new reports of atrocities committed against women.

“It is a shame for humanity… that sexual violence occurs in all conflicts,” he said.

“If we don’t fight impunity, I think the future is bleak.”

AFP