AFP

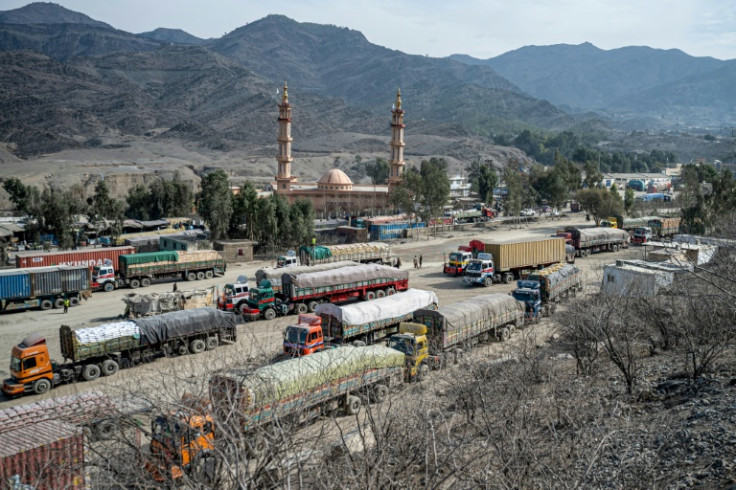

A dusty logjam of trucks inches across a rut in the mountains splitting Pakistan and Afghanistan, teeming with a cargo of fruit and coal — and paying the Taliban authorities for the privilege of passage.

In downtown Kabul, a patrol of accountants inspects a bazaar, billing shopkeepers for trading honey, hair conditioner and gas hobs under the snapping white flag of the country’s new rulers.

Afghanistan is frozen deep in a second winter of humanitarian turmoil since the Taliban seized power in 2021, but cash is changing hands at a dizzying pace.

The Taliban administration is proving adept at collecting tax — and seemingly without the corruption associated with the previous administration.

At Torkham on the border, one trucker told AFP that under the old regime he would pay 25,000 Afghani ($280) at illegal checkpoints along a 620 kilometre (380 mile) trip to Mazar-i-Sharif.

“Now we travel day and night, and no one asks us to pay,” said 30-year-old driver Najibullah.

In late January, the World Bank reported “strong” revenue collection at 136 billion Afghani ($1.5 billion) over the first nine months of 2022 — broadly in line with the final full year of the US-backed regime.

“It has been reported quite consistently that they’re doing quite well on revenue, and that too is happening when economic activity is quite subdued,” an official with a foreign organisation in Afghanistan told AFP.

“It was a shock.”

However, in a country where the United Nations says half the citizens face severe hunger, the figures beg many questions.

About 60 percent of the Taliban treasury is funded by customs, the World Bank says, raised at tumbledown checkpoints like Torkham in eastern Nangarhar province, where truckers trade rubber-stamped paperwork for cash.

Incoming freight is mostly food — oranges, potatoes and World Food Programme (WFP) flour — but the outgoing lane is dominated by a convoy of lavishly painted trucks loaded with chromite and coal.

Neighbouring Pakistan has been hammered by the global energy crisis caused by the war in Ukraine at a time when an economic crisis has withered its dollar reserves.

So it brokered a deal to pay for Afghan coal in rupees — cutting out usual suppliers in South Africa and Indonesia.

According to a 2022 report by research group XCEPT, coal exports to Pakistan likely doubled under the Taliban government and earned Afghanistan $160 million in tax — three times what the previous administration was capable of.

But the mining industry relies heavily on child labour, with punishingly low pay and the barest safety measures.

“This has been their strategy from day one — to increase revenue no matter what,” former deputy commerce and industry minister Sulaiman Bin Shah told AFP.

The Taliban’s lodestar has always been law and order — albeit on their ultra-conservative terms — and there are signs Kabul’s coffers have benefitted from a crackdown on corruption which leeched the US-backed government for 20 years.

Afghanistan climbed 24 places up Transparency International’s corruption perception ranking last year, a rare case of a metric improving for the country.

“Afghanistan has that capacity, which now we are collecting,” said finance ministry spokesman Ahmad Wali Haqmal.

“The main problem was the corruption.”

But analyst Torek Farhadi sees it another way.

“They are more effective because people are scared of them,” he said.

“The Taliban have an iron grip on the administration. They have the guns, and nobody can steal any money.”

The Taliban’s transition from insurgents to bureaucrats is not entirely surprising.

During their 20-year guerilla war, they established a shadow government in many areas they controlled, including courts, regional governors and a tax system to fill their war chest.

Afghanistan’s customs director Abdul Matin Saeed once ran shadow toll booths for the insurgency in Farah province, bordering Iran, and Balkh, bordering Uzbekistan, roving the territory on raspy motorbikes to evade capture.

“We didn’t have complete control over the roads… but still we were meeting our ends,” he told AFP.

This experience was “very handy” when the republic fell and he took office in Kabul, he says.

The government’s ability to raise revenue has far-reaching implications.

The international community has pressured the regime over restrictions on women’s rights with financial sanctions, but their ability to raise domestic revenue grants them greater independence.

It also presents a dilemma for donors — does providing humanitarian support free up the Taliban administration to pursue discretionary aims such as quashing dissent?

But perhaps the most glaring issue is the lack of clarity over how all this cash is spent.

Last year the Taliban government issued an annual budget outlining 231 billion Afghanis of spending, but scant further detail.

“This money goes to the functioning of the government of the Taliban,” said analyst Farhadi.

“I want to see how they spent it. Where did it go?”

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP