U.S. firms developing a new generation of small nuclear power plants to help cut carbon emissions have a big problem: only one company sells the fuel they need, and it’s Russian.

That’s why the U.S. government is urgently looking to use some of its stockpile of weapons-grade uranium to help fuel the new advanced reactors and kick-start an industry it sees as crucial for countries to meet global net-zero emissions goals.

“Production of HALEU is a critical mission and all efforts to increase its production are being evaluated,” a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) said.

The energy crisis triggered by the war in Ukraine has renewed interest in nuclear power. Backers of smaller, next-generation reactors say they are more efficient, quicker to build, and could turbocharge the shift away from fossil fuels.

But without a reliable source of the high assay low enriched uranium (HALEU) the reactors need, developers worry they won’t receive orders for their plants. And without orders, potential producers of the fuel are unlikely to get commercial supply chains up and running to replace the Russian uranium.

“We understand the need for urgent action to incentivize the establishment of a sustainable, market-driven supply of HALEU,” the DOE spokesperson said.

The U.S. government is in the final stages of evaluating how much of its inventory of 585.6 tonnes of highly enriched uranium to allocate to reactors, the spokesperson said.

The fact that Russia has a monopoly on HALEU has long been a concern for Washington but the war in Ukraine has changed the game, as neither the government nor the companies developing the new advanced reactors want to rely on Moscow.

HALEU is enriched to levels of up to 20%, rather than around 5% for the uranium that powers most nuclear plants. But only TENEX, which is part of Russian state-owned nuclear energy company Rosatom, sells HALEU commercially at the moment.

While no Western countries have sanctioned Rosatom over Ukraine, mainly because of its importance to the global nuclear industry, U.S. power plant developers such as X-energy and TerraPower don’t want to be dependent on a Russian supply chain.

“We didn’t have a fuel problem until a few months ago,” said Jeff Navin, director of external affairs at TerraPower, whose chairman is billionaire Bill Gates. “After the invasion of Ukraine, we were not comfortable doing business with Russia.”

CHICKEN AND EGG

Nuclear power currently generates about 10% of the world’s electricity and many countries are now exploring new nuclear projects to improve their energy supply and energy security, as well as to help meet goals for cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

But with large-scale projects still challenging for reasons including huge up-front costs, project delays, cost overruns and competition from cheaper energy sources such as wind, several developers have proposed so-called small modular reactors (SMR).

While the SMRs on offer from companies such as EDF and Rolls-Royce use existing technology and the same fuel as traditional reactors, nine out of 10 of the advanced reactors funded by Washington are designed to use HALEU.

Proponents say these advanced plants need less frequent refuelling and are three times as efficient as traditional models. Some analysts say this means they will ultimately overtake conventional nuclear technology, though the designs have yet to be tested on a commercial scale.

The average levelised cost of electricity – the price needed for advanced projects to break even – is $60 per megawatt-hour compared with $97 for conventional plants, according to data from research group the Energy Innovation Reform Project.

Some analysts say the price difference might be narrower at the moment, because the smaller advanced reactors using HALEU don’t yet have economies of scale from mass production.

Companies in the United States and Europe have plans to produce HALEU on a commercial scale but even in the most optimistic scenarios, they say it would take at least five years from the point they decide to proceed.

And this chicken and egg conundrum is complicating the smooth development of HALEU supply.

“Nobody wants to order 10 reactors without a fuel source, and nobody wants to invest in a fuel source without 10 reactor orders,” said Daniel Poneman, chief executive of U.S. nuclear fuel supplier Centrus Energy Corp.

For firms interested in new advanced reactors, such as Washington state’s public utility Energy Northwest, fuel supplies are certainly an issue in the decision making process.

“A reliable HALEU supply is one of many factors under consideration,” the company said in an emailed statement.

ALTERNATIVE SUPPLIES

The U.S. government recognised years ago that Russia’s monopoly on HALEU could hamper the development of the advanced reactors it hopes will provide low-carbon energy at home and also be exported to markets in Europe and Asia.

The government awarded a shared-cost contract in 2019 to Centrus, the only company outside Russia which currently has a licence to make HALEU, to build a demonstration facility.

While the facility was due to start making HALEU this year, production has been put back to 2023, partly because of delays in getting hold of storage containers due to supply chain issues during the global pandemic, Centrus said.

Once the facility gets up and running, it will take five years before Centrus can start producing 13 tonnes of HALEU a year. But that’s only a third of the amount the DOE projects will be needed for U.S. reactors by 2030.

TerraPower, for example, said it will need 15 tonnes of HALEU for the first fuel load of its advanced reactor.

Other potential HALEU producers are further behind.

French state-owned uranium mining and enrichment company Orano says it could start producing HALEU in five to eight years, but will only apply for a production licence once it has customers with long-term contracts.

In a response to a DOE request for information about how to establish a programme to support HALEU production, Orano said it would be down to the U.S. government to kick-start the industry.

“Orano’s assessment shows that the single most important factor enabling success is the DOE guaranteeing a certain volume of demand,” the company said in a statement on its website.

European uranium enrichment company Urenco, meanwhile, says it is considering sites in the United States and Britain for HALEU production but has yet to apply for licences.

CLOCK IS TICKING

For TerraPower and X-energy, which have projects planned in the U.S. states of Wyoming and Washington respectively, the clock is ticking.

Washington awarded them contracts to build two demonstration rectors by 2028 and shared the costs. But without Russian fuel, that deadline will fall well before any alternative commercial suppliers would be up and running.

While the 20% enrichment levels for HALEU are well below the roughly 90% level needed for weapons, companies need special licences to produce it. Additional security and certification requirements are also required for production sites, packaging and transportation of the fuel.

To speed up the process and break the deadlock, the U.S. government is looking to “downblend” weapons-grade highly enriched uranium sitting in its stockpile, though that will also take time.

The U.S. government said in 2016 it had downblended 7.1 tonnes between Sept. 30, 2013 and March 31, 2016. Asked this month whether the process had become any faster, the DOE said: “Downblending rates are consistently evaluated for acceleration opportunities.”

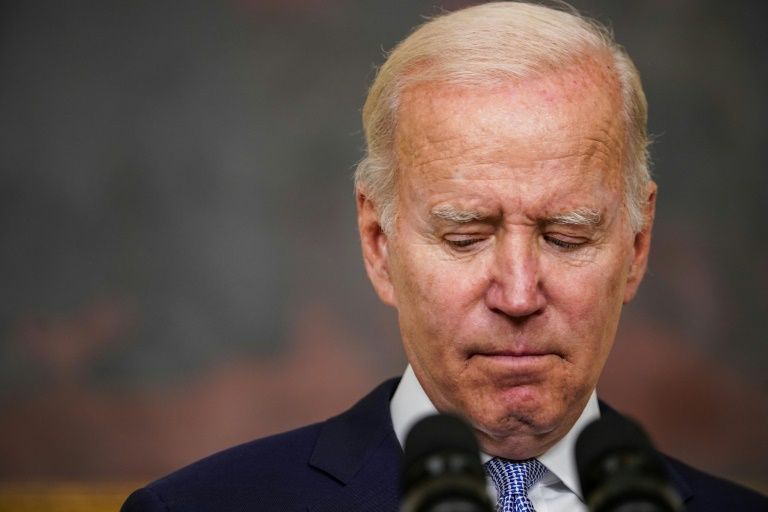

The Inflation Reduction Act U.S. President Joe Biden signed in August contained $700 million to secure HALEU supplies from the government and a consortium partnered with the DOE for use in advanced reactors and research.

In September, the White House asked Congress for another $1.5 billion in a temporary government funding bill to boost domestic supply of low enriched uranium and HALEU, to address potential difficulties in accessing Russian fuel.

Lawmakers took the measure out of the bill over concerns about costs, though it remains a priority for some Biden officials, including Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm.

Last year, nuclear power stations in the United States imported about 14% of their uranium from Russia, along with 28% of their enrichment services, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

![Jermaine Burton: Alabama Wide Receiver Caught on Camera Hitting Rival Fan’s After Team’s Shocking Loss [WATCH]](https://data.ibtimes.sg/en/full/62687/jermaine-burton.jpg)