Long dependent on fossil fuels before emerging a champion of offshore wind power, Danish company Orsted is now struggling to restore its business after dropping several major projects.

Orsted was dealt a $4 billion blow last year when it cancelled wind farm projects in the United States, a crucial market for the group.

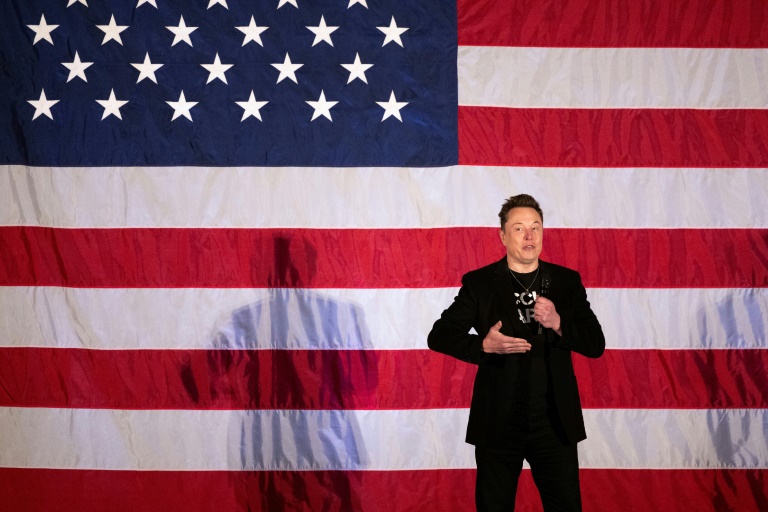

The return of Donald Trump, who dislikes wind power, to the White House in January could prove another challenge for the company.

Orsted recently announced it was withdrawing from the Danish government’s “Green Fuels for Denmark” project, and it has asked shareholders to share the burden and suspended dividends until the 2026 financial year.

“A few years ago, they had the ambition of being a major green actor but now we don’t hear that they want to change the world,” climate editor Jakob Martini of business newspaper Finans told AFP.

Orsted is seeking to refocus on offshore wind and “earn money from that core business”, said Martini, who has been following the sector for several years.

Supply chain disruptions, high interest rates, rising material costs, falling electricity prices and political uncertainties have all rocked Orsted.

Orsted was once considered a success story.

In less than a decade — from 2010 to 2019 — it went from a traditional energy company that relied on fossil fuels for energy production to instead have 86 percent come from renewable sources.

“They won projects that created a lot of value,” Tancrede Fulop, an analyst at Morningstar, told AFP.

It was the first company to invest massively in offshore wind power in the United States, securing fixed-price projects in a low-rate environment.

“With Covid, the acceleration of the energy transition, interest rates kept at zero and the election of (US President Joe) Biden, they benefitted from a favourable bubble,” Fulop said.

But “in the United States, which is a new market and therefore more risky, they may have bitten off more than they can chew,” he added.

Central banks in the United States and Europe started raising interest rates in 2022 efforts to tame inflation, and only began to lower them this year.

Martini said that Orsted “lacked foresight” when it bid on huge offshore projects in the United States “without hedging against high interest rates”.

When abandoning the Ocean Wind 1 and 2 projects, two wind farms that were due to be installed off the coast of New Jersey, the group was also forced to reimburse its suppliers.

“It was a colossal cancellation. It completely wiped them out,” Fulop said.

Now it faces more uncertainty with Trump’s return.

“What Trump hates most is offshore wind power, but the two projects which Orsted is involved in, Revolution Wind and Sunrise Wind, have received federal approval, so Trump can’t block them,” Fulop said.

In any case, the day after his re-election, Orsted shares, which have lost 70 percent of their value since the end of 2021, fell by over 12 percent.

“There are a lot of concerns linked to this election when Orsted still hasn’t recovered from the wounds of 2023,” said Jacob Petersen, an analyst at Sydbank.

“Things will be better when Trump is in charge and we know what he wants to do,” Petersen added.

According to analysts, a ray of hope is Norwegian energy giant Equinor’s acquisition of nearly 10 percent of Orsted’s shares, making it the second-largest shareholder after the Danish state.

“It’s a blessing, a sign of confidence,” Petersen said.

Fulop noted that the acquisition was made “before the American election, so they don’t think it’s an issue, so it’s quite positive”.

Orsted is also gradually replenishing its coffers and recently sold half the Changhua 4 offshore wind farm to Taiwan’s Cathay Life Insurance for around $1.6 billion.

Despite current headwinds, wind power is predicted to have a bright future.

The rate of global wind capacity expansion is poisted to double between 2024 and 2030 compared to the previous six year, according to the International Energy Agency.

“Cleantech continued to grow through the last Trump presidency, and we are confident that it will continue to grow through this one. Because it is cheaper and local and drives energy security,” Kingsmill Bond, an energy strategist at US think tank Rocky Mountain Institute.