AFP

China, which chairs a high-stakes UN biodiversity summit in Montreal, is due to present a long-awaited compromise text on Sunday in an attempt to seal the “peace pact with nature” that the planet sorely needs.

More than 10 days of fraught biodiversity negotiations look to be coming to a head as delegates prepare to wrangle over the compromise draft agreement.

“It is not a perfect document, not a document that will make everyone happy, however it is a document that is based on the efforts of all of us over the last four years,” said China’s Environment Minister Huang Rinqiu.

“It is a document that must be adopted at this meeting that is highly expected by the international community.”

Observers had warned the COP15 conference risked collapse as countries squabbled over how much the rich world should pay to fund the efforts, with developing countries walking out of talks at one point.

But conference leaders turned upbeat Saturday on their chances of securing a deal.

Huang said he was “greatly confident” of a consensus and his Canadian counterpart Steven Guilbeault said “tremendous progress” had been made.

Huang said he would publish a draft agreement at 8:00 am EST (1300 GMT) on Sunday and hear lead delegates’ feedback later in the day.

The negotiations officially run until December 19, but could go longer if needed.

“Now is not the time for small decisions, let’s go big!” tweeted French President Emmanuel Macron.

“Let’s work together to achieve the most ambitious agreement possible. The world is depending on it.”

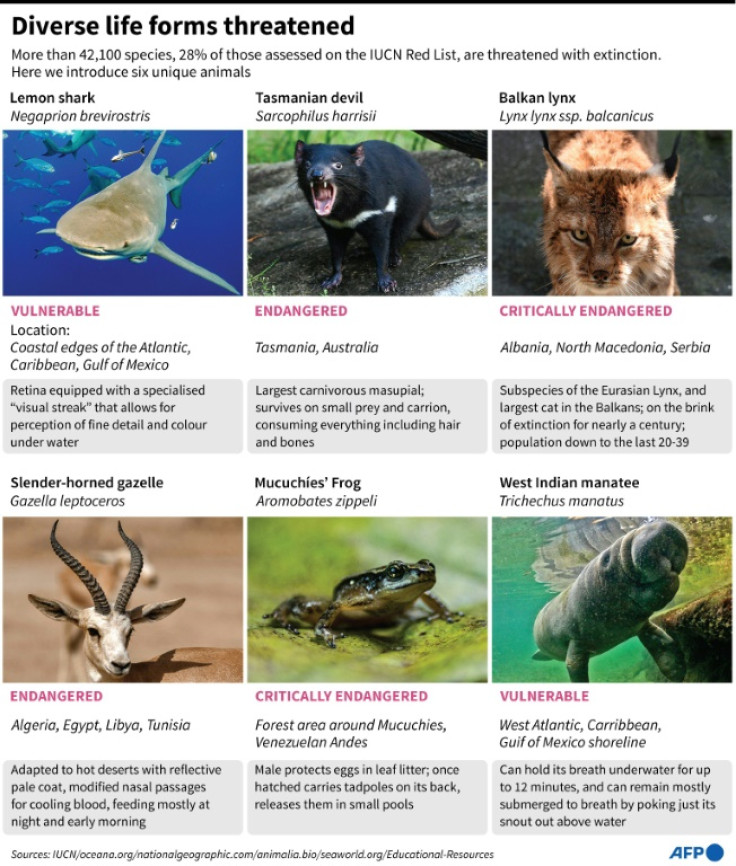

Delegates are working to roll back the destruction and pollution that threaten an estimated one million plant and animal species with extinction, according to scientists that report to the UN.

The text is meant to be a roadmap for nations through 2030. The last 10-year plan, signed in Aichi, Japan in 2010, did not achieve any of its objectives — a failure blamed widely on its lack of monitoring mechanisms.

Major goals in the draft under discussion include a cornerstone pledge to protect 30 percent of the world’s land and oceans by 2030.

The more than 20 targets also include reducing environmentally destructive farming subsidies, requiring businesses to assess and report on their biodiversity impacts, and tackling the scourge of invasive species.

Representatives of Indigenous communities, who safeguard 80 percent of the world’s remaining biodiversity, want their rights to practice stewardship of their lands to be enshrined in the final agreement.

“We are the ones doing the work. We protect biodiversity,” said Valentin Engobo, leader of the Lokolama community in the Congo Basin, in a statement released by Greenpeace. “You won’t replace us. We won’t let you.”

The issue of how much money the rich countries will send to the developing world, home to most of the world’s biodiversity, has been the biggest sticking point.

Several countries have announced new commitments. The European Union has committed seven billion euros ($7.4 billion) for the period until 2027, double its prior pledge.

But campaigners and developing countries say more is needed — and delegates have not reached agreement on what form the new funding flows should take.

Brazil has proposed flows of $100 billion annually, compared to the roughly $10 billion at present.

“We will be able to specify our financial ambitions once we have seen the text,” France’s Environment Minister Christophe Bechu told AFP on Saturday.

“An agreement on paper without numbers would be worse than no agreement. We need an ambitious agreement that is quantified and with verifiable aims and dates.”

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP