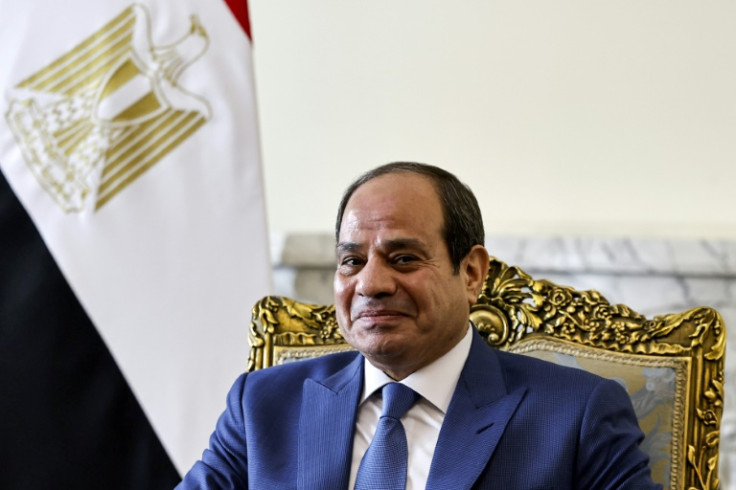

Ten years after President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi rose to power in Egypt promising prosperity for all, he embarks on a third run for office as Egyptians buckle under unrelenting economic strain.

In July 2013, then-army chief Sisi, wearing his uniform and trademark dark glasses, went on television asking for “a mandate” to fight “terrorism” after the army toppled democratically elected but divisive Islamist president Mohamed Morsi.

The following month, security forces forcibly dispersed two pro-Morsi protest camps in Cairo in an operation that killed more than 700 people.

Sisi secured a mandate at the ballot box the following year, and was re-elected in 2018.

On Monday, he announced he will “again heed the people’s call” and run in December, while thousands of supporters celebrated in ready-built stages across the Arab world’s most populous country.

Sahar Abdelkhalek, a teacher who escorted a bus full of her students to a rally in western Cairo, is grateful.

“All around us, countries collapsed and never recovered, but because of our president and our army, we’re moving forward,” she said.

Sisi won with nearly 97 percent of the vote in his first election, and by a similar margin last time. He is widely expected to emerge victorious again in the historically autocratic country.

But with Egyptians struggling to survive during their nation’s worst-ever economic crisis, Sisi’s defining ethos might not be as persuasive as it once was, both domestically and amongst the country’s allies.

For his supporters, including the state’s sizeable media machine, he is still the “hero” who stamped out “terrorism”, after massive crowds protested Morsi’s rule.

His backers laud Sisi for restoring Egyptians’ sense of safety and prioritising massive development projects, the biggest being a $58 billion New Administrative Capital in the desert east of Cairo.

Experts call it a “vanity” project.

What Sisi describes as his “New Republic” revolves around his image as a visionary maverick, priding himself on personally overseeing state development funds and directing government spending — including to “eradicate Hepatitis C”, once a devastating epidemic in the country.

But the 68-year-old rules “alone, and is blamed alone” for the country’s woes, according to veteran human rights activist Hossam Bahgat.

The currency has lost half its value since March 2022, pushing inflation to a record-breaking 39.7 percent in the import-dependent economy.

Born in November, 1954 in Cairo’s El-Gamaleya neighbourhood, Sisi graduated from Egypt’s military academy in 1977. He later studied in Britain and the United States.

The former military intelligence chief has four children, including Mahmoud, a high-ranking officer in state intelligence.

During his early years in power, Sisi’s popularity was so great that supporters put his face on vehicles, products and even baked goods in what they called “Sisimania.”

He adopted the image of “the father of the nation”, soft-spoken and most often seen seated with a microphone in hand, presiding over public ceremonies.

But Egyptians now sense they are being increasingly reproached.

He has told them to “stop talking nonsense” about an economy they do not understand, to tolerate “hunger and deprivation” for prosperity, and consider “donating blood” to shore up their income.

The president has suffered “a cross-class loss of legitimacy,” Bahgat said, even among hardline supporters who have become disillusioned after watching their life savings disappear with the weakening currency.

While Egyptians express their frustration online, some of Sisi’s once supportive international allies have cooled, experts say.

Most world capitals “have lost confidence” in his economic model, according to Robert Springborg, of the Italian Institute of International Affairs.

At the core of his model is “militarisation” and “profligate borrowing for prestige projects with limited economic benefits” that formerly generous Gulf allies are no longer willing to fund, Springborg said.

Gulf states have begun demanding reform and returns on their investments, “no longer believing there is political will within this leadership to change anything,” according to independent analyst Hafsa Halawa.

“There is now genuine frustration, if not outright anger.”

According to rights groups, tens of thousands of dissidents have been arrested during his rule, for criticising the government as well as even for complaining online about inflation.

Authorities have jailed one of Sisi’s potential challengers in the election, Hisham Kassem, and rights groups say dozens of supporters of another, Ahmed al-Tantawi, have been detained.

On the campaign trail, Tantawi has called Sisi “Egypt’s worst leader in 200 years.”

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP