AFP

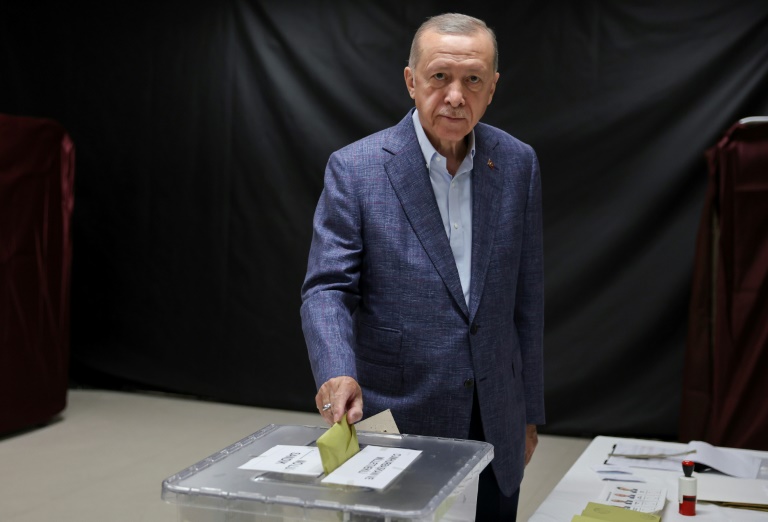

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan cruises on Sunday into the final week before an historic runoff election as the big favourite to extend two decades of his Islamic-rooted rule until 2028.

Secular leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu gave the opposition’s best performance of Erdogan’s dominant era in May 14 parliament and presidential polls.

The retired bureaucrat of Kurdish Alevi descent broke ethnic barriers and Erdogan’s stranglehold on the media and state institutions to win almost 45 percent of the vote.

But Erdogan still came within a fraction of a point of topping the 50-percent threshold needed to win in the first round.

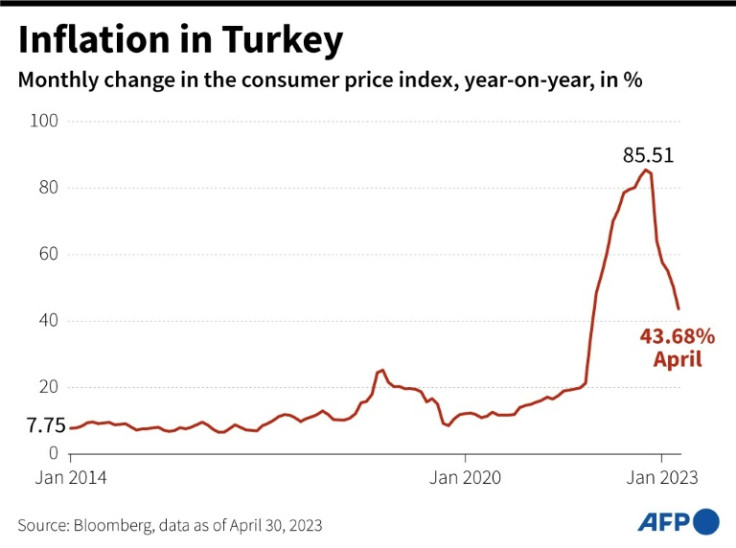

The 69-year-old leader did it despite Turkey’s worst economic crisis since the 1990s and opinion surveys showing him headed for his first national election defeat.

Kilicdaroglu will now need to rally his deflated troops and beat the odds yet again to wrest back power for the secular party that ruled Turkey for most of the 20th century.

The Eurasia Group consultancy put Erdogan’s chances of winning next Sunday at 80 percent.

“It will be an uphill struggle for Kilicdaroglu in the second round,” Hamish Kinnear of the Verisk Maplecroft consulting firm agreed.

Erdogan rode a nationalist wave that saw smaller right-wing parties pick up nearly 25 percent of the parallel parliamentary vote.

Kilicdaroglu is courting these voters in the second presidential round.

The 74-year-old revamped his campaign team and tore up his old playbook for the most fateful week of his political career.

He has replaced chatty clips that he used to record from his kitchen with desk-thumping speeches and pledges to immediately rid Turkey of millions of migrants.

“As soon as I come to power, I will send all the refugees home,” he said in his first post-election address.

He has chased the endorsement of a little-known ultra-nationalist, whose tiny vote share pushed Turkey into its first presidential runoff.

And he has punched back against Erdogan’s claims that he was associating with “terrorists” — a code word for Kurdish groups fighting for broader autonomy in Turkey’s southeast.

“We have millions of patriots to reach,” Kilicdaroglu said.

But Kilicdaroglu’s sharp right turn could prove costly with voters from Kurdish regions that overwhelmingly backed him in the first round.

Kurds embraced Erdogan during his first decade in power because he worked to lift many of their social restrictions.

They turned against him when Erdogan formed his own alliance with Turkey’s nationalist forces and began to unleash purges after surviving a failed coup attempt in 2016.

Kilicdaroglu’s new and more overtly nationalist tone echoes a secular era during which Kurds — who make up nearly a fifth of Turkey’s population — were stripped of basic rights.

The political battles are being accompanied by market turmoil that set in once it became apparent that Erdogan was on course to keep his grip on power.

Turkey’s recent years have been roiled by economic upheaval that erased many of the gains of Erdogan’s more prosperous early rule.

Most of the problems stem from Erdogan’s fervent fight against interest rates — an approach some analysts link to his adherence to Islamic rules against usury.

“I have a thesis that interest rates and inflation are positively correlated,” he told CNN this week.

“The lower the interest rates, the lower inflation will be.”

The markets’ trust in more conventional economics have put massive pressure on the lira.

Government data showed Turkey’s foreign currency reserves — topped up by aid from Arab allies — dropping by $9 billion and reaching their lowest levels in 21 years in the week running up to the first-round vote.

Analysts think most of the money was spent on efforts to prop up the lira against sharp and politically sensitive falls.

“There is now a very real risk that an Erdogan victory could lead to macroeconomic instability in Turkey, including the threat of a severe currency crisis,” Capital Economic warned.

But Erdogan has exuded confidence since the first round.

He has ridiculed his rival’s nationalist overtures and stuck by some of his more controversial policies — including an increasingly strong relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Erdogan’s turn towards Russia has helped secure billions of dollars of relief on Turkey’s huge energy bill.

“Russia and Turkey need each other in every field possible,” Erdogan told CNN.

He also argued that his more “balanced” stance towards Putin helped him negotiate a UN-backed deal with Russia under which Ukraine was allowed to resume exporting grain.

“This was possible because of our special relationship with President Putin,” Erdogan said.

He also scoffed at remarks from 2019 by US President Joe Biden — recalled by Erdogan’s allies throughout the campaign — calling Erdogan an “autocrat”.

“Would a dictator ever enter a runoff election?” Erdogan asked.

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP