Voters across Europe cast ballots Sunday on the final — and biggest — day of elections for the EU’s parliament, with far-right parties expected to make gains at a pivotal time for the bloc.

“In the current world situation, where everyone is trying to isolate each other, it’s important to keep standing up for peace and democracy,” said one voter in Berlin, Tanja Reith, 52.

A male voter in his 70s in Stockholm, who gave only his first name as Tommy, said his pressing electoral concern was immigration, specifically “many people coming from Africa and so on”.

With global warming, “it’s too hot to live there so they want to go where the climate is not so hard,” he said.

Polling stations opened Sunday in 21 EU countries, including heavy hitters France and Germany, for a vote that helps shape the European Union’s direction over the next five years.

Polling came as the continent is confronted with Russia’s war in Ukraine, global trade and industrial tensions marked by US-China rivalry, a climate emergency and a West that within months may have to adapt to a new Donald Trump presidency.

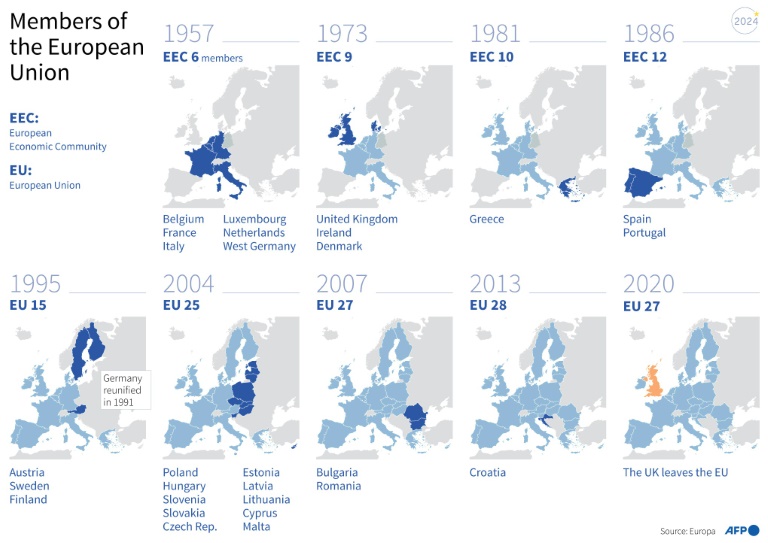

More than 360 million people were eligible to vote across the EU’s 27 nations in the elections that started Thursday — although only a fraction are expected to cast their ballots.

The outcome will determine the makeup of the EU’s next parliament. The legislature helps decide who runs the powerful European Commission, with German conservative Ursula von der Leyen vying for a second term in charge.

While centrist mainstream parties are predicted to hold most of the incoming European Parliament’s 720 seats, polls suggest they will be weakened by a stronger far right pushing the bloc towards ultraconservatism.

Preliminary results are expected late Sunday.

Many European voters, hammered by a high cost of living and some fearing immigrants to be the source of social ills, are increasingly persuaded by populist messaging.

Hungarian voter Ferenc Hamori, 54, said he wanted more EU leaders like his country’s right-wing premier Viktor Orban — even though he expected Orban to remain “outnumbered in Brussels”.

Outside his polling station, Orban framed the vote as a “pro-peace or pro-war election”.

The Hungarian leader — whose government takes on the rotating EU presidency from July — maintains close relations with President Vladimir Putin and has stoked fears of the Ukraine war expanding to one between the West and Russia, blaming Brussels and NATO.

In EU countries closest to Russia, the spectre of Russia’s threat loomed large.

“I would like to see greater security,” doctor Andrzej Zmiejewski, 51, said after voting in Poland’s capital Warsaw.

In Romania’s capital Bucharest, psychologist Teodora Maia said she cast her vote “on “the theme of war, which worries us all, and ecology”.

France will be the EU’s high-profile battleground for competing ideologies.

With voting intentions above 30 percent, Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally (RN) is predicted to handily beat President Emmanuel Macron’s liberal Renaissance party, polling around half that.

In the French city of Lyon, 83-year-old Albert Coulaudon said Macron was getting “mixed up” in too many international issues such as the war in Ukraine.

“That scares me,” he told AFP.

A smiling Le Pen voted in her her northern French village of Henin-Beaumont, pausing on the way to wave and accept flowers from supporters but making no comment to media.

French turnout at midday (1000 GMT) was slightly higher than in the 2019 EU elections, at 19.8 percent, according to official figures.

In Germany, Europe’s biggest economy, the election could also deal a blow to Chancellor Olaf Scholz.

Leading the German polls are the opposition centre-right Christian Democrats, with a projected 30 percent of votes. The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), on 14 percent, was seen either neck-and-neck or ahead of all three parties in Scholz’s ruling coalition: the SPD, the Greens and the liberal FDP.

In Italy, holding its second day of voting, the far-right ruling Brothers of Italy party of Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni was expected to come out on top.

Meloni is being courted both by von der Leyen — who needs her backing to clinch a second commission mandate — and Le Pen and Orban who are eyeing the formation of a far-right supergroup in the European Parliament.

Unlike Le Pen, however, Meloni aligns with the EU consensus on maintaining military and financial assistance to Ukraine.

Mainstream leftist parties fear that a sharp rightward turn in the EU parliament could result in even tougher immigration rules for the bloc and a watering down of climate policies.

But there has been some backlash against the surge in populism and in Hungary’s Orban faced a challenge from former government insider Peter Magyar.

“I think the public sentiment has changed; people who have been burying their heads in the sand are now standing up and coming forward,” said voter Dorottya Wolf in Budapest.

The main far-right grouping, the European Conservatives and Reformists, in which Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party sits, was projected to win 76 seats.

The smaller Identity and Democracy grouping that includes Le Pen’s RN was predicted to get 67.

AFP

AFP

AFP