Reuters

The U.S. central bank should continue raising interest rates on the back of recent data showing inflation remains persistent while the broader economy seems poised to continue growing, even if slowly, St. Louis Federal Reserve President James Bullard said.

In comments countering views that the U.S. is heading towards a banking crisis, a recession, or both in the near future, Bullard told Reuters in an interview: “Wall Street’s very engaged in the idea there’s going to be a recession in six months or something, but that isn’t really the way you would read an expansion like this.”

Investors may see rate cuts in the Fed’s near future, part of a recession-breeds-accommodation view of the world, but “the labor market just seems very, very strong. And the conventional wisdom is that if you have a strong labor market that feeds into strong consumption … and that’s a big chunk of the economy … it doesn’t seem like the moment to be predicting that you have a recession in the second half of 2023,” he said.

Despite the current 3.5% unemployment rate, Fed staff at the central bank’s March 21-22 policy meeting said they also anticipate a “mild recession” this year, while Bullard’s colleagues have penciled in an economic outlook that indicates zero growth or a contraction for much of the rest of the year after a relatively strong first quarter.

In the case of the staff forecast, the fallout from recent stress in the banking sector seemed to tip the scales.

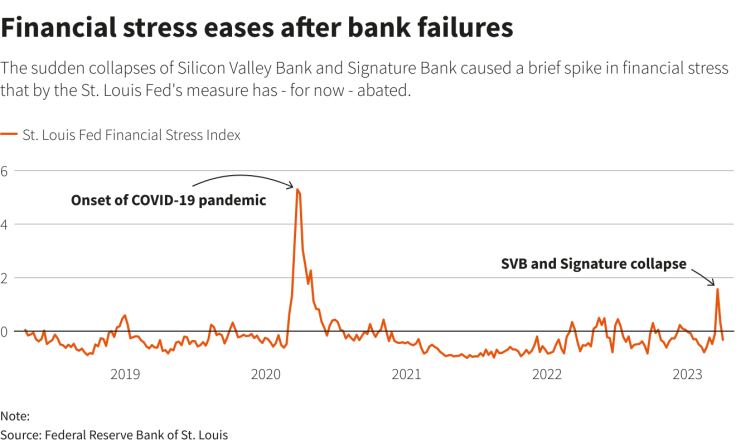

But if two U.S. bank failures last month were going to spark a crisis, Bullard said, it’d likely be showing up in things like the St. Louis Fed’s financial stress index. The index did spike after the March 10 collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, but it quickly reverted to a normal reading.

“If you were really going to get a major financial crisis out of this, that index would spike up to a four or five. It’s zero now. So it doesn’t look, as of this moment, like too much is happening,” Bullard said.

(Graphic: Financial stress eases after bank failures,

)

HIGHER TERMINAL RATE

Bullard’s remarks stake out the aggressive side of a debate underway at the Fed about how to calibrate the final steps of an historically fast rate hiking cycle against both evidence that underlying inflation is not falling very fast towards the central bank’s 2% target, and signs the economy is slowing under the “bite” of the rate increases approved so far.

Measures like the Dallas Fed trimmed mean inflation rate have been flat over several months, an indication – depending on the point of view – of underlying inflation still more than double the Fed’s target that needs to be squelched, or of the delayed impact of monetary policy still to be felt.

The bulk of Fed policymakers as of March felt one more rate increase, which would raise the benchmark overnight interest rate to a range between 5.00% and 5.25%, was all that would be needed. That could come at the Fed’s May 2-3 meeting.

While agreeing that the tightening cycle may be close to the finish line, Bullard feels the policy rate will need to rise another half of a percentage point beyond that level, to between 5.50% and 5.75%.

Some policymakers and analysts worry it is those final steps that could push the economy into a recession. And beyond the rate hike decision next month, the Fed will have to send some signal about what happens next – whether to keep the language in the current policy statement that “some additional policy firming may be appropriate,” or point to a pause.

(Graphic: Rates and inflation,

)

LIMIT GUIDANCE

Given how inflation and the economy are behaving, Bullard said, the fewer promises made the better.

“You want to be responsive to incoming data through the summer into the fall,” he said. “You wouldn’t want to be caught giving forward guidance that said we’re definitely not doing anything and then have inflation coming in too hot or too sticky.”

Once interest rates are at a level considered “sufficiently restrictive” to slow inflation, Bullard said he felt “the bias would be higher for longer” to be sure it is fully under control.

It won’t, he argues, require a large increase in the unemployment rate to do the job, a view that melds hawkishness on inflation with relative bullishness on where the economy is heading.

But it will take more time for people, businesses and local governments to spend through their pandemic-era savings, and, as that spending slows, for price competition among firms to curb inflation over time.

Recession forecasts “are coming from models that put too much weight on the idea that interest rates went up quickly,” Bullard said. “What about the strong labor market? What about that feeding consumption? … What about the pandemic money still to be spent off, both at the state and local level and at the individual household level?

“Inflation is coming down, but not as fast as Wall Street expects.”

Reuters

Reuters