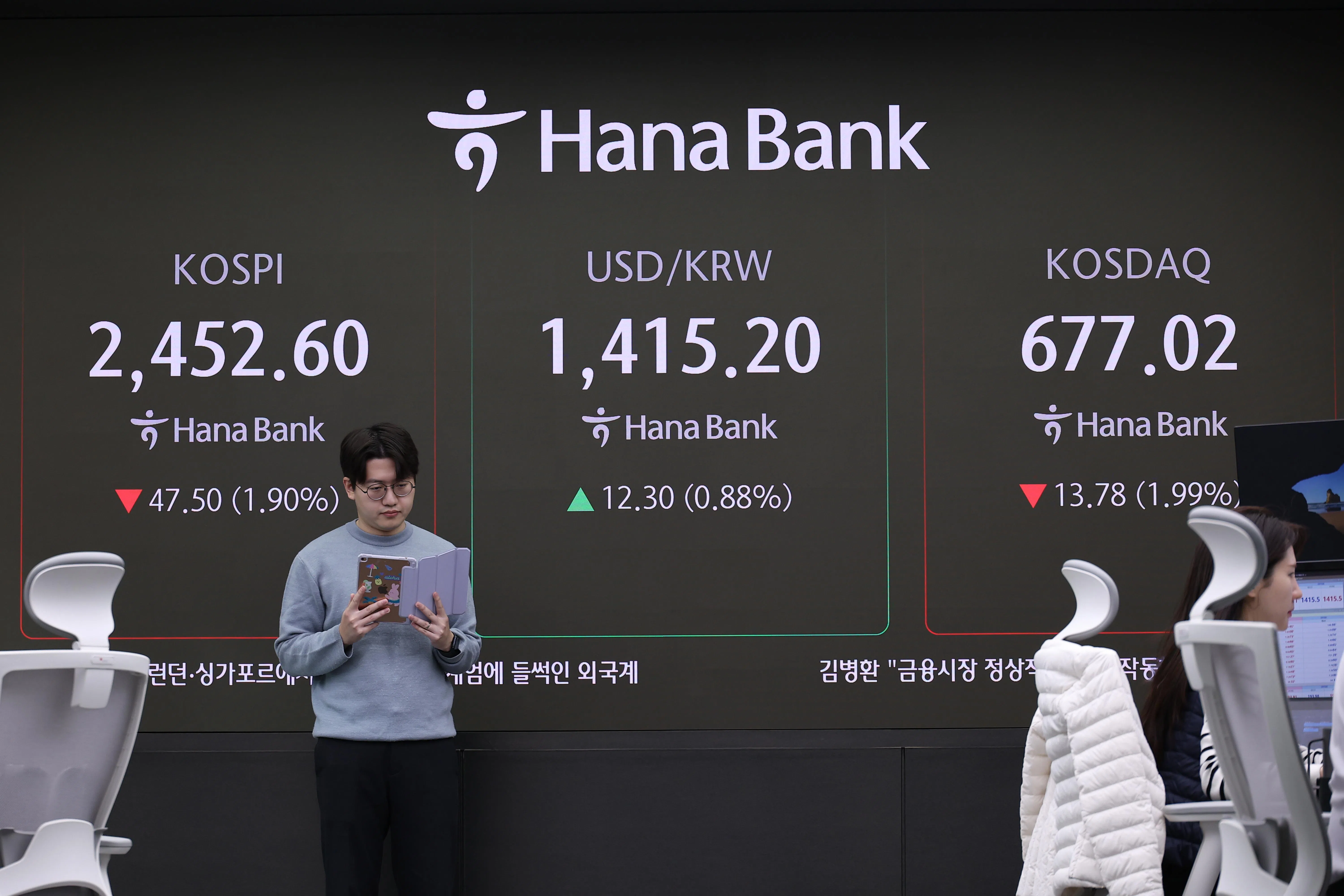

SOUTH Korean shares slumped Wednesday (Dec 4) after President Yoon Suk Yeol’s shock declaration of martial law overnight. This was the first since 1979 in Asia’s fourth-largest economy and global tech powerhouse. Even though he lifted that hours later, uncertainty reigns, as calls grow for his resignation or impeachment.

The country has had a history of martial law, which was imposed in 1948, 1952 and 1979.

What is martial law?

It refers to temporary rule by military authorities. Declared during times of emergencies such as war, natural disasters and civil unrest, martial law is in place when civil authorities are deemed unable to function.

Under martial law, the military assumes the authority to enforce laws, manage public order and ensure national security. All existing laws are suspended, along with civil authority and the ordinary administration of justice. This could lead to the suspension of civil liberties, censorship of media and curfews.

The military can also establish mandatory checkpoints, search any suspicious person, confiscate belongings, and even evict individuals from their homes without a warrant. There is usually no limitation how long martial law could last because its use is determined by necessity.

BT in your inbox

Start and end each day with the latest news stories and analyses delivered straight to your inbox.

How does it affect business and economic activity?

Investor sentiment and confidence typically takes a hit when a country imposes martial law for a number of reasons.

First, the ability and credentials of the military regime to manage the economy may be unclear. If the key leaders do not have the requisite business experience or qualifications, investor activity would typically slow.

Next, the suspension of civil liberties and imposition of curfews that are usual features of martial law, also do no favours to consumer sentiment. In such a climate, consumers are likely to cut back on discretionary spending. The limits on movements could also affect logistical operations such as at ports, disrupting supply chains.

Further hurting business and consumer confidence would be media censorship. If the credibility of news and data is in doubt, investors might not be as ready to pump in funds.

The uncertainty and jolt to sentiment could affect banking functions as well. To prevent a run on the bank situation as nervous consumers withdraw their bank deposits, the regime is likely to slap withdrawal caps. It often also imposes curbs on foreign currency transactions, which could include a complete ban, to stem depreciation in its currency that typically accompanies the announcement of martial law. For instance, the Korean won Tuesday tumbled to its lowest in more than two years against the US dollar. While it has recovered on Wednesday, MayBank analysts said the won could remain under pressure.

Further afield, an example of banking limits enforced under martial law is Ukraine. It capped cash withdrawals and imposed strict forex controls when it declared martial law, following Russia’s invasion in February 2022. These included limiting the repatriation of dividends by Ukrainian companies to their overseas investors. Some of them have subsequently been relaxed.