Reuters

Federal Reserve policymakers expect to raise U.S. interest rates further, and keep them high for longer, than they had earlier anticipated, signaling Wednesday that squashing high inflation will likely take a bigger toll on the economy and the job market than they had hoped.

And though Fed Chair Jerome Powell said that the Fed’s latest policymaker projections don’t necessarily mean the economy will fall into a recession, he did suggest the risk is worth it, and that the Fed has no plans to cut rates to cushion the blow.

“Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth and some softening of labor conditions,” Powell said.

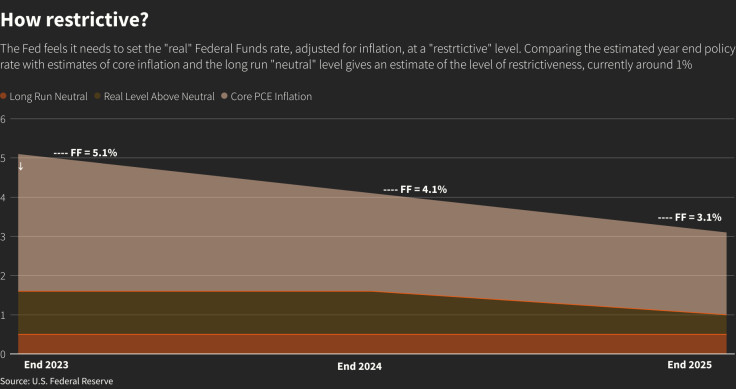

U.S. central bankers see the policy rate, now in the 4.25%-4.5% range after Wednesday’s 50-basis-point increase, rising to 5.1% by the end of next year, according to the median estimate in the Fed’s quarterly summary of economic projections published at the end of its two-day meeting.

That is a half percentage point higher than they forecast in September.

The rate is then seen dropping to 4.1% in 2024, the projections show, again higher than estimated just three months ago.

There was broad disagreement among central bankers about that decline, with seven of the 19 policymakers expecting the rate not to drop as fast, and five seeing a steeper decline.

Meanwhile they expect it to take longer to get to the Fed’s 2% inflation goal. The projections show inflation by the Fed’s preferred measure – the personal consumption expenditures price index, currently running at 6% – cooling to 3.1% in the final quarter of next year and to 2.5% by the end of 2024.

In September, policymakers expected inflation to register 2.8% at the end of 2023 and 2.3% at the end of 2024.

RESTRICTIVE

The Fed has said it plans to tighten policy until it is “sufficiently restrictive” to bring inflation down, and this year lifted rates more aggressively than it has done in 40 years to get to that point.

Though the Fed is getting “close,” Powell said Wednesday, it is not there yet. That is in part because despite two months of data showing some “welcome” cooling, inflation looks set to start 2023 higher than central bankers had thought, he said.

That means rates will need to go higher to keep up, Powell signaled.

How restrictive?

And though keeping rates steady while inflation declines actually means policy is getting increasingly restrictive, that will not be the test for letting up, he said.

“I wouldn’t see us cutting rates until the Committee is confident that inflation is moving down to 2% in a sustained way,” he said in his clearest rebuke yet of what has been persistent market expectations for rate cuts in the second half of 2023.

Policymakers expect their interest-rate hikes to push the unemployment rate, now at 3.7%, to 4.6% in the final quarter of 2023, and stay there through 2024. Three months ago, the jobless rate was seen rising to 4.4%.

By one measure, known as the Sahm Rule for former Fed staffer Claudia Sahm, an increase of that magnitude in the unemployment rate likely signals a recession.

In any event, assuming a relatively stable labor force, an increase of that size would swell the ranks of the unemployed by more than a million people.

Wednesday’s projections show Fed policymakers have become more pessimistic about the outlook for economic growth, with a median projection for GDP growth next year of 0.5%, versus September’s expectation for 1.2%. Two Fed policymakers see the economy shrinking next year.

Taking the GDP forecast and the unemployment forecast together, said BNP Paribas economist Carl Riccadonna, “it is very clearly recession.”