AFP

This year will be the fourth year running that Seyi Anne Moses has had to decide against going home to see her parents at Christmas.

Like many urban Nigerians, Moses dreads the long road journey to see relatives in the countryside — a trip fraught with danger as gangs lurk to attack travellers or hold them to ransom.

Moses, 44, hails from the central Nigerian state of Kogi but lives with her three children in Lagos, the country’s economic capital.

“I have decided again that I won’t travel home this year due to the insecurity, the murders, the kidnappings and the rapes,” she said.

“When I see the pictures of wounded or killed people in the social media, I become afraid. Most roads are not safe.”

The year-end holiday season has given many Nigerians cause to ponder their country’s deep security problems and worsening economy as the clock ticks to presidential elections two months away.

President Muhammadu Buhari — who had come to office on a campaign vow to improve lives and end violence — is stepping down after serving two terms, the constitutional maximum.

In this country of 215 million people, not a week goes by without kidnappings and massacres making headlines.

“There are more than 10,000 casualties per year from armed gangs in parts of Nigeria, coupled with kidnapping rings operating along the main routes,” said Ikemesit Effiong at consultancy SBM Intelligence.

“No region in Nigeria is spared,” added Effiong, who said he was lucky to have been able to visit his grandparents in his home state of Akwa Ibom two years ago.

Insecurity is endemic in Nigeria, Africa’s biggest economy and most populous country.

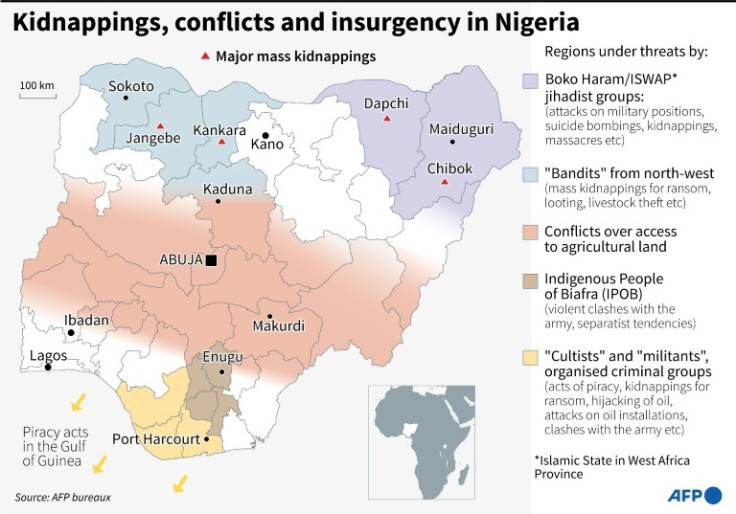

Armed gangs known as bandits are ravaging the central and northwest regions of the country, jihadist groups are active in the northeast and the southeast has been rocked by separatist unrest.

Local media publish maps of the most dangerous roads to avoid during Christmas.

According to the World Bank, 87 percent of rural roads are in poor condition.

The gunmen take advantage of this to attack travellers and kidnap them, especially near forests which are used as hideouts.

Travellers who thought the train was safe were stunned when in March this year a train travelling from the capital Abuja to the northwestern city of Kaduna with 970 people onboard was attacked by gunmen, who kidnapped scores of VIP passengers.

Just as prominent in people’s minds is the shrinking standard of living. Inflation is running at more than 21 percent — the worst since 2005.

For the third year in a row, John Ishaya, 33, will not return to his father and brother living in the northeast.

A driver, he earns the equivalent of just $105 a month. With prices soaring, his meagre salary no longer allows him to take the road — let alone fly.

“I never used a plane in my life,” he said.

“The value of the currency collapsed, income has receded, businesses are closing and unemployment and underemployment represents more than half of the workforce,” Effiong said.

“Flights have almost doubled,” he said.

“Even by Nigerian standards, I would not be surprised if this one is not a very Merry Christmas”

Along with India, Nigeria has the highest number of people living in extreme poverty in the world.

According to the latest official figures, 63 percent of Nigerians — 133 million people — suffer from “multidimensional poverty,” a metric which includes child mortality, access to electricity and clean water.

Sandra Akusu, from the southeastern state of Benue where her parents live, will remain alone in Lagos at the end of the year.

The 19-year-old earns $85 a month.

“I did not plan for anything this year and my birthday is on the 25th, imagine!” she said. “The way the things are right now, it is so hard.”

AFP

AFP

AFP

![Dramatic Videos Capture Fans Jumping onto Argentina Team Bus as Victory Parade is Cut Short and Messi and Company are Evacuated by Helicopter [WATCH] Dramatic Videos Capture Fans Jumping onto Argentina Team Bus as Victory Parade is Cut Short and Messi and Company are Evacuated by Helicopter [WATCH]](https://data.ibtimes.sg/en/full/64062/argentina-fans.jpg)