AFP

Dressed in a full-body protective suit, an elderly pest control worker could last no more than 15 minutes spraying pesticide along a Hong Kong pavement before the summer heat became too much.

“The longer you work, the more it feels like it’s raining inside the (suit)… it’s just like being in a sauna,” said Wah, 63, who asked to be identified only by his first name.

He emerged from his protective clothing drenched in sweat on a scorching August morning, with temperatures soaring to 32.2 degrees Celsius (90 degrees Fahrenheit) and humidity hitting 87 percent.

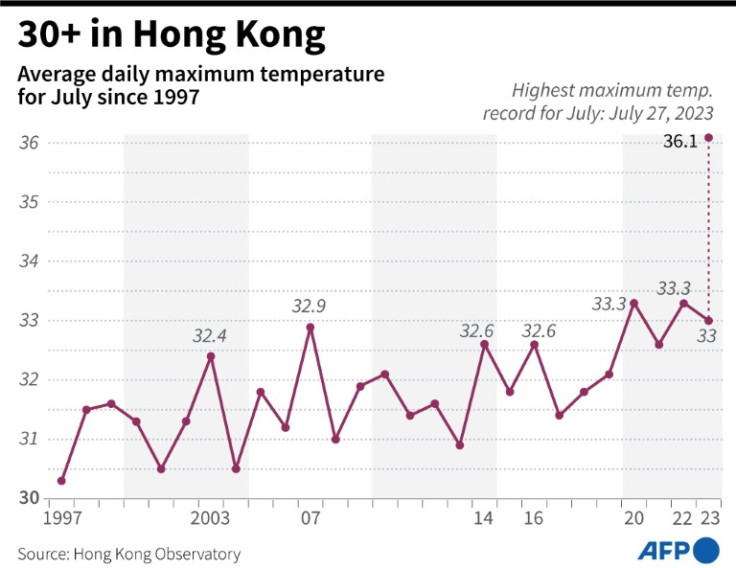

The month before, Hong Kong saw its third-hottest July on record, with the maximum daily temperature hitting 36.1 degrees Celsius. The top three warmest years in the city’s history were all recorded after 2018.

Recently, the government advised employers to let workers take longer breaks on hotter days, but companies say the guidelines fail to consider the needs of different work environments.

Activists argue that without strong regulations, thousands of Hong Kong workers remain vulnerable to heat-related illnesses.

“Temperatures in 2022 broke multiple records, so we felt more support was needed,” said social worker Fish Tsoi of Caritas Hong Kong.

She is part of a research team measuring the body temperatures of people toiling under extreme heat, especially the elderly like Wah and his six-person crew.

Last July, a pest control firm saw 20 of its workers quit because conditions were too tough, while 10 were hospitalised with heatstroke, she said.

“This situation did not just appear last year — it was years in the making,” Tsoi said. “Nobody took proactive steps to respond.”

Temperatures around the world are rising to unprecedented levels, with more frequent heatwaves, which scientists have partly attributed to human-caused climate change.

A city infamous for its intense humidity levels, Hong Kong introduced a heat-stress warning system in May to help employers schedule “appropriate work-rest periods”.

It has been issued more than 50 times since then.

Greenpeace campaigner Tom Ng said the “biggest problem” was that employers who ignore the guidelines face no legal repercussions.

“In terms of how climate change affects Hong Kongers, outdoor workers are at the frontlines,” he told AFP.

Emily Chan, a public health specialist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, welcomed the guidelines but agreed more was needed.

She pointed to mainland Chinese cities, including neighbouring tech hub Shenzhen, which mandate work stoppages and subsidies once temperature thresholds are reached.

“(Hong Kong) has been relatively slow in setting up protections,” Chan said.

Labour minister Chris Sun said this month that his department had “stepped up inspections” and would issue warnings to employers when needed.

Despite the new system having no legal bite, the government can still sue employers “who just turn a blind eye”, he said in May.

Wah, who clocks six-day weeks for $8 an hour, said there is little he can do to avoid heat exhaustion besides operating his machinery in short bursts.

“If you do this for more than half an hour, the human body cannot withstand the temperature,” he said.

In each of the past four years, the city has logged fewer than two dozen cases of heatstroke-related work injuries and no deaths, according to labour officials, but activists dispute those statistics.

“The reality is (heatstroke) is not reported,” said Fay Siu, who runs the Association for the Rights of Industrial Accident Victims.

Either the workers do not know they can report it or “the company may not recognise it”, she told AFP.

She pointed to a 2018 case when a 39-year-old died after fainting at a construction site. An investigation found rhabdomyolysis — a potentially life-threatening type of muscle breakdown — “caused by high temperatures and signs of heatstroke”.

“But the insurance company and his employer… pinned it on his personal medical conditions so it would not be categorised as a work injury,” Siu said.

Her group has identified at least four cases of outdoor workers dying on days of extreme heat in the past year.

Siu said labour officials should do more to investigate or family members would be left with “no recourse”.

In response, the Labour Department said there was no information indicating that workers were unable to report heatstroke-related work injuries, but agreed that cases with “mild symptoms” may go unreported.

“The number of registered cases may be lower than the actual number of symptomatic cases,” the department told AFP in a statement.

“Based on the experience of the (department) in processing work injuries suspected to be relating to heat stroke, employers generally do not dispute their liabilities and would make compensation,” they added.

For some, the government’s new heat-stress warning system appears to have had limited impact.

Wah and his colleagues say they have seen few changes to their routine — especially since they risk having their pay docked if they are caught taking lengthy breaks.

Chuen, 70, said they usually continue working after a five-minute water break.

“That’s how it goes,” he said, sweating in the shade.

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP