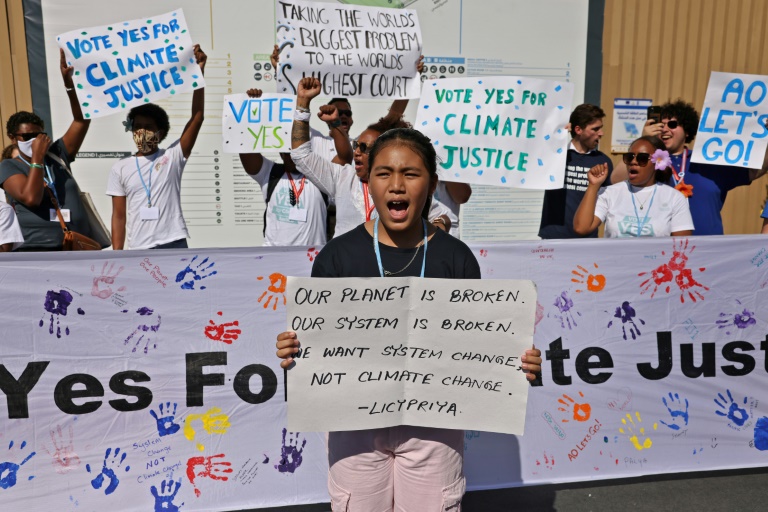

Seeking to speed up global efforts against climate change, Vanuatu is leading efforts to get the International Court of Justice involved, a move praised by activists at UN talks.

The COP27 climate summit in Egypt has been dominated by calls for nations to redouble their efforts to cut emissions and for rich polluters to finally provide the money that developing nations need to cope with global warming.

Threatened by rising sea levels, the small Pacific island of Vanuatu signalled last year that it would seek a non-binding “advisory opinion” from the Hague-based ICJ.

A year later, the initiative was formally launched at the UN General Assembly, which will have to vote on whether to back it in the next few months.

“I say let the gavel fall. Let judges inspire our leaders to act and let justice be done,” Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate said at the COP27 meeting in the Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh.

Speaking to some 100 world leaders attending a summit on Tuesday, Vanuatu President Nikenike Vurobaravu said the initiative had grown into a coalition of 85 countries.

“Clearly, something is not working,” Vurobaravu said, noting that emissions are rising, climate financing remains “wholly inadequate” and the ambitious goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius may not be met.

“I appeal in the strongest terms to leaders here at COP27 to vote in favour of the ICJ resolution at the UN General Assembly so that we can finally put human rights at the centre of climate decisions,” Vurobaravu said.

Vanuatu’s UN ambassador, Odo Tevi, said the goal is to “clarify the rights and obligations of states under international law as it pertains to the adverse effects of climate change”.

Vanuatu also wants the ICJ to “clarify the due diligence requirements relating to climate action for emitters of greenhouse gases — past, present and future,” he said.

The question could irk developed countries that have historically been the biggest emitters of greenhouse gases but reject the idea of paying reparations to developing nations for the losses caused by natural disasters.

The issue of “loss and damage” is at the forefront of the COP27 talks that are scheduled to end on Friday.

Yeb Sano, executive director at Greenpeace Southeast Asia, said Vanuatu’s effort has “generated so much excitement” and global support.

“The international community needs clarity of purpose and this campaign is a beacon of hope that has the power to breathe new life… into the multilateral negotiations,” Sano said.

A similar effort more than a decade ago by another Pacific island, Palau, fizzled. But times have changed, with a slew of climate-related disasters this year highlighting the urgency the planet faces.

Though a legal opinion by ICJ would not be binding, Vanuatu hopes it would shape international law for generations to come.

Margaretha Wewerinke-Singh, an assistant professor of public international law at Leiden University in the Netherlands, said the ICJ can provide “legally relevant guidance” that is “very likely to be followed” by courts around the world.

While the Paris Agreement targets for emissions reduction are not binding, she said an ICJ opinion could signal that there are “legal obligations for taking action on climate change and legal consequences when these obligations are breached”.

Perhaps more importantly, she added, an ICJ opinion could “inspire more ambitious climate action” from governments and big companies.

Harjeet Singh, a senior adviser at the Climate Action Network, said ICJ hearings on the matter would generate “much awareness” around climate change.

“It’s a matter of survival,” he told AFP.