In a schoolroom, young Liberians take it in turns to draw an image expressing what they fear most as they become eligible to vote for the first time.

One of the 18- to 25-year-olds depicts a man on the ground, tears rolling down his face, as his neighbour stands over him holding the crime weapon.

Entitled “war”, the image sums up what many worry about most: a return to violence.

The fear is never far from the surface in a country scarred by back-to-back civil wars.

Between 1989 and 2003, the conflicts in the West Africa nation left more than 250,000 people dead.

Liberians will vote in presidential and parliamentary elections on Tuesday, in what the main political parties have pledged will be a peaceful process.

But the killing of three people on Friday in clashes between supporters of the two main political parties have fuelled fears.

“What is violence?” asks Nehemiah Jallah, 24, who is behind the initiative aimed at promoting peace.

He is leading the workshop being held at a school in the city of Buchanan, about 150 kilometres (just over 90 miles) east of the capital Monrovia.

“Violence is when you force somebody to do something,” one of those listening responds.

“It’s when you are seeking to do harm,” suggests another.

Jallah pulls no punches in telling his young audience seated at wooden desks to stay clear of any form of violence.

“Know that when violence escalates, buildings will be destroyed, innocent people will be killed,” he said.

“I don’t know which political party you are from, but make sure to vote peacefully and do not do it with violence.

“As Liberia is peaceful, so let us hold the peace of Liberia during and after the election.”

Some of the first-time voters wonder how they should behave in the event of claims of cheating during the election.

The discussion is lively.

On the walls of the room, posters advocate non-violence with messages such as “Liberia needs me so I must keep her safe from violence”.

“The court is the best place to solve election disputes”, reads another.

More than 60 percent of Liberians are under 25 years old.

“Politicians are trying to use you because they know that you are more vulnerable,” said Lawrence Sergbou, who introduces himself as a youth activist to the audience.

Liberia’s civil wars were notorious for the use of child soldiers, he said, adding that violence decimates hope for development.

“When we look at social networks, listen to the radio, see the country’s history… Yes, I’m afraid,” Sergbou acknowledged.

“We’ve been living peacefully for 20 years now and we don’t want that to end.”

No war criminals have been prosecuted within Liberia since the two civil wars came to an end in 2003.

Several former warlords still play an influential role in the country’s politics.

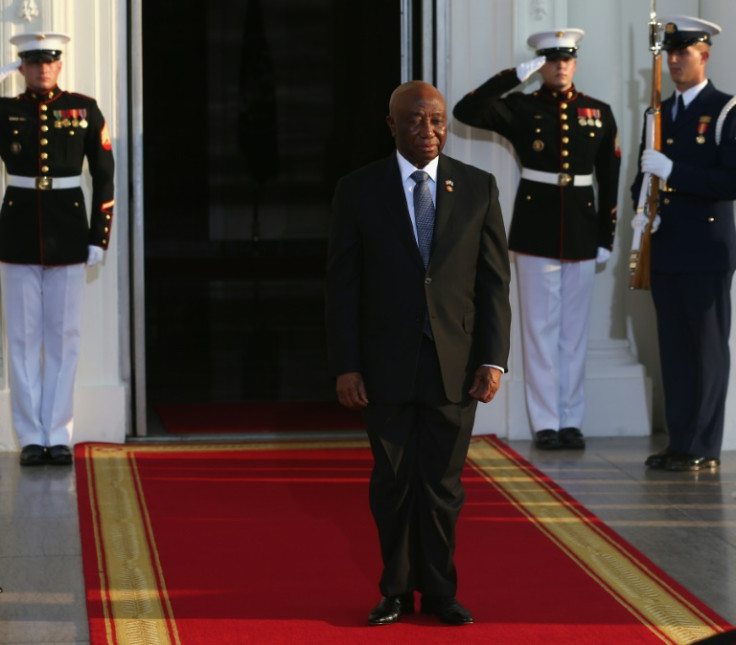

One of them, 71-year-old Prince Johnson, a senator, has teamed up in an alliance with candidate Joseph Boakai.

Johnson has threatened a popular revolt if the ruling party manipulates the elections.

Boakai, who was vice president between 2006 and 2018, is among the frontrunners for the presidency.

He has indicated that any vote cheating or manipulation will lead to “the end of this country”.

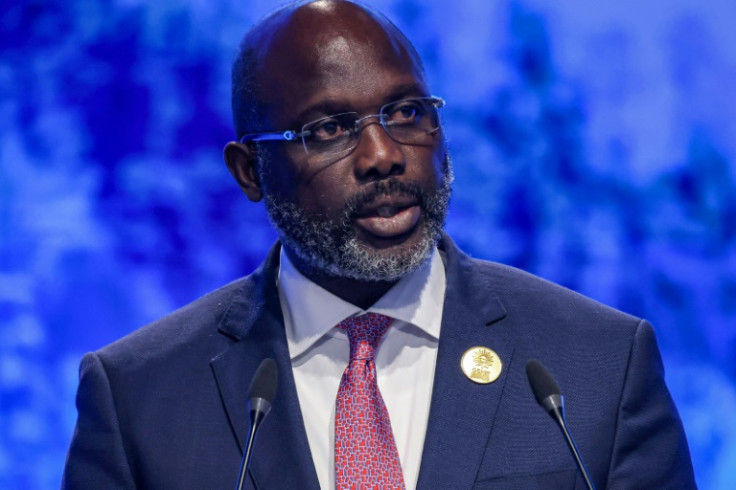

President George Weah, a former international football star who is running for a second term, has promised peaceful, fair and credible elections.

All parties vying in the polls pledged in April under the aegis of the United Nations and the West African bloc, ECOWAS, to refrain from violence and resolve electoral disputes through legal institutions.

AFP

AFP

AFP

![Ryan Carson: Chilling Video Captures Moment Social Activist and Poet Is Stabbed to Death While Waiting at NYC Bus Stop with Girlfriend [WATCH]](https://data.ibtimes.sg/en/full/70237/ryan-carson.jpg)