AFP

A library in Israeli-annexed east Jerusalem offers a rare glimpse into Palestinian history with its treasure trove of manuscripts dating back hundreds of years before the creation of Israel.

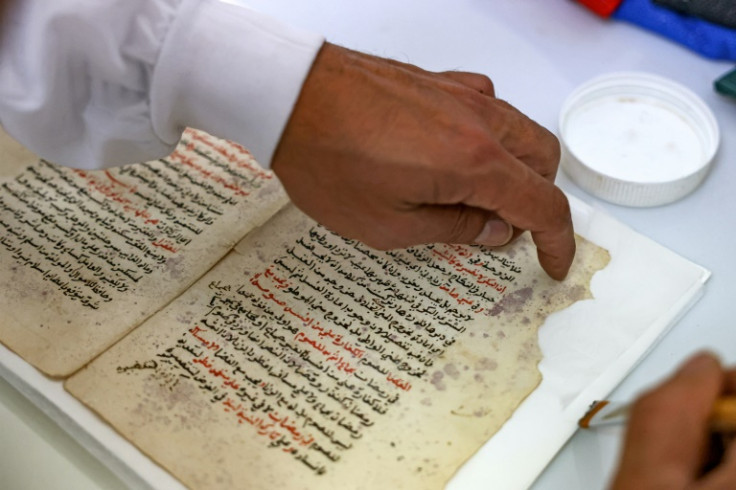

At the Khalidi Library in the walled Old City, Rami Salameh expertly inspects a damaged manuscript as part of the effort to restore and digitise historical Palestinian documents.

“The manuscripts range from jurisprudence to astronomy, the Prophet’s (Mohammed) biography and the Koran,” says the Italian-trained restorer as he carefully manoeuvres a dry brush over a fragile text on Arabic grammar.

From his small workshop, he lets out a sigh of relief, concluding that it won’t be necessary to treat the 200-year-old document for discolouration as a result of oxidation.

Working alone, Salameh has already restored 1,200 pages from over a dozen manuscripts belonging to private Palestinian libraries over the past two and a half years.

The items date back as far as 300 years, to the Ottoman period.

The majority of the manuscripts come from the Khalidi Library itself, the largest private collection of Arabic and Islamic manuscripts in the Palestinian territories.

Also on its shelves are Persian, German and French books, including an impressive collection of titles by French writer Victor Hugo.

Located in the Old City near one of the entrances to the Al-Aqsa mosque compound, the library was founded by Palestinian judge Raghib Al-Khalidi in 1900.

From its main building, which overlooks the Western Wall — the holiest site where Jews can pray — warring sultans reportedly played a role in liberating Jerusalem from the Crusaders in the 12th and 13th centuries.

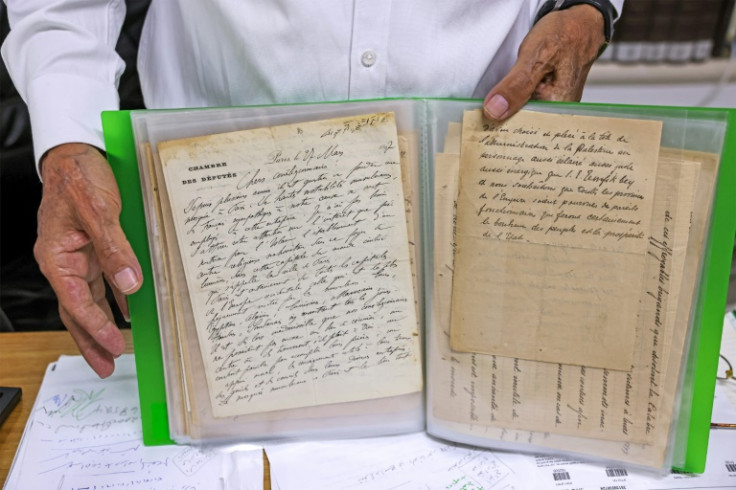

The collection contains books, correspondence, Ottoman decrees and newspapers, including documents from the influential Khalidi family.

They offer a rich view of past life in the holy city, with the oldest book dating back to the 10th century.

“We have manuscripts that talk about the cultural and social status of the people of Jerusalem, and this is an indication of the presence of Palestinians here for centuries,” says librarian Khader Salameh, the restorer’s father who manages the collection.

“The contents of the library negate the Zionist claim that this country was empty,” he added, referring to the common refrain that the land was unpopulated prior to the creation of Israel in 1948 and the expulsion of over 750,000 Palestinians.

Palestinian families and institutions in east Jerusalem have frequently been evicted to make way for Israeli settlements since Israel captured and annexed the area, including the Old City, in the 1967 Six-Day War — moves regarded as illegal by the UN and the international community.

Part of the library was seized by Israeli settlers to build a Jewish religious school, the librarian lamented.

The library’s administration waged a long legal battle to fight the settlement, but did not succeed in preventing the seizure of part of it.

Khader Salameh said the outcome could have been much worse, and the entire property taken by settlers, had it not been for the support they received.

“Israeli intellectuals supported the library administration and testified in court in our favour,” he noted.

Ever since, the library has continued to preserve cultural heritage in Jerusalem through their restoration and digitisation, with support from local and international organisations.

“We capture the documents with very high precision without exposing the paper to light, as the manuscripts are very delicate, and we want to preserve them for as long as possible,” says Shaimaa al-Budeiri, a digital archive officer.

Surrounded by hundreds of books and equipment in her office, she brushes pages clean before placing them flat to photograph and upload the images onto her computer.

To date, Budeiri has photographed around 2.5 million pages of manuscripts, newspapers, rare books and other documents from the four private libraries in Jerusalem.

She says digitisation is the way forward, as it allows researchers remote access to the library’s archive.

They hope to secure more funding for the restoration work to buy costly supplies and equipment, including acid-free storage boxes.

They also want to update the workshop to safeguard against the humidity that threatens their work with the delicate manuscripts.

Budeiri says it is her love for books that drives her passion for her work.

“If I see someone holding a book in a violent way, I feel like the book is in pain,” she notes.

“The book gives to you, it doesn’t take away from you.”

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP