Mangosuthu Buthelezi, the once-feared Zulu nationalist and historic leader of Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP) which presided over South Africa’s deadliest violence ahead of the first all-race elections, died Saturday aged 95, President Cyril Ramaphosa announced.

“I am deeply saddened to announce the passing of Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi … Traditional Prime Minister to the Zulu Monarch and Nation, and the Founder and President Emeritus of the Inkatha Freedom Party.” Ramaphosa said in a statement.

“Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi has been an outstanding leader in the political and cultural life of our nation, including the ebbs and flows of our liberation struggle, the transition which secured our freedom in 1994 and our democratic dispensation,” Ramaphosa said.

Born of royal blood on August 27, 1928, Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi was to some the embodiment of the Zulu spirit: proud and feisty. To others, he bordered on a warlord.

For years he was defined by his bitter rivalry with South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC), a party that was his political home until he broke away to form IFP in 1975.

He led the party from its inception, a reign marked by bloody territorial battles with ANC supporters in black townships during the 1980s and 1990s that left thousands dead.

In 2019, aged 90, he stepped down as party leader after 44 years at the helm, describing a “long” and “difficult” journey he had travelled.

“It was not my own decision to remain as party president for many years, but (we are) democrats, when my party unanimously asked me to lead, I accepted,” he said in August 2019.

The IFP, initially formed as a cultural organisation, draws its support base from country’s largest ethnic group, the Zulus.

As premier of the “independent” homeland of KwaZulu, a political creation of the apartheid government, Buthelezi was often regarded as an ally of the racist regime.

He was dogged by allegations of collaborating with the old government to fuel violence to derail the ANC’s liberation struggle — a claim he furiously denied.

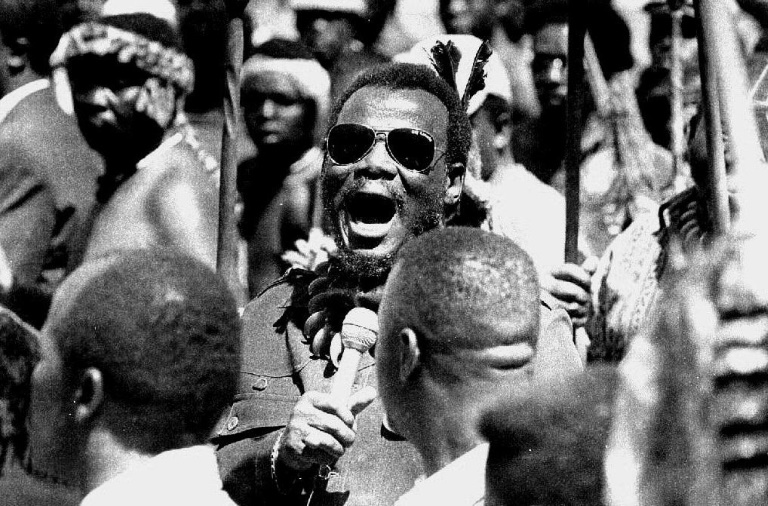

The bespectacled and slender chief would sometimes lead marches of shield- and spear-wielding IFP supporters through the streets of Johannesburg and Durban, clad in traditional leopard skin regalia.

In the 1980s, the rift between his party and the ANC intensified as he distanced himself from the party and its anti-apartheid strategies, denounced by then-jailed Nelson Mandela as undermining the black leadership.

He also stirred the wrath of the liberation movements by calling for increased international investment in South Africa, opposing the call for sanctions to put pressure on the white government.

Violence between Inkatha supporters and rival liberation groups escalated in the mid-1980s. By 1990 more than 5,000 people had been killed in clashes.

In 1991, Mandela and Buthelezi held talks and called for an end to the bloodshed.

But a year later, reports resurfaced of IFP-fomented violence, backed by apartheid security forces in Johannesburg and in the eastern Natal region.

A charismatic speaker with a heavy stutter, Buthelezi blamed the ANC for the unrest that threatened to become a full-blown civil conflict, which the apartheid government garishly referred to as “black-on-black” violence.

“Bull… it’s all bull… I am a Christian and all my life have been committed to the precepts of Christianity,” Buthelezi responded to claims that his supporters fanned the violence.

There was a new surge of unrest between ANC and IFP supporters in the run up to the first democratic elections in 1994, that claimed about 12,000 lives.

Buthelezi threatened to boycott the poll, saying that it would be “impossible” for IFP to participate, but he changed his mind a week before, after frantic interventions.

The IFP went on to win control of the newly formed province of KwaZulu-Natal and fared decently in Johannesburg.

But support for his party dwindled over the years, marred by leadership squabbles with calls for his removal as party leader to make way for new blood.

In the first non-racial elections in 1994, the IFP won 43 seats — but its showing had plummeted to just 14 seats in the May 2019 vote.

The violence largely dissipated after 1994, with Buthelezi appointed home affairs minister. He went on to become one of the longest-serving lawmakers.

In September 1998, while then-president Mandela was out of the country and Buthelezi was acting president, he authorised an ill-fated military invasion of Lesotho.

Buthelezi is also listed in the Guinness World Records as having made the longest speech to a legislative assembly with an address in March 1993 over 11 days, with an average of two-and-a -half hours each day.

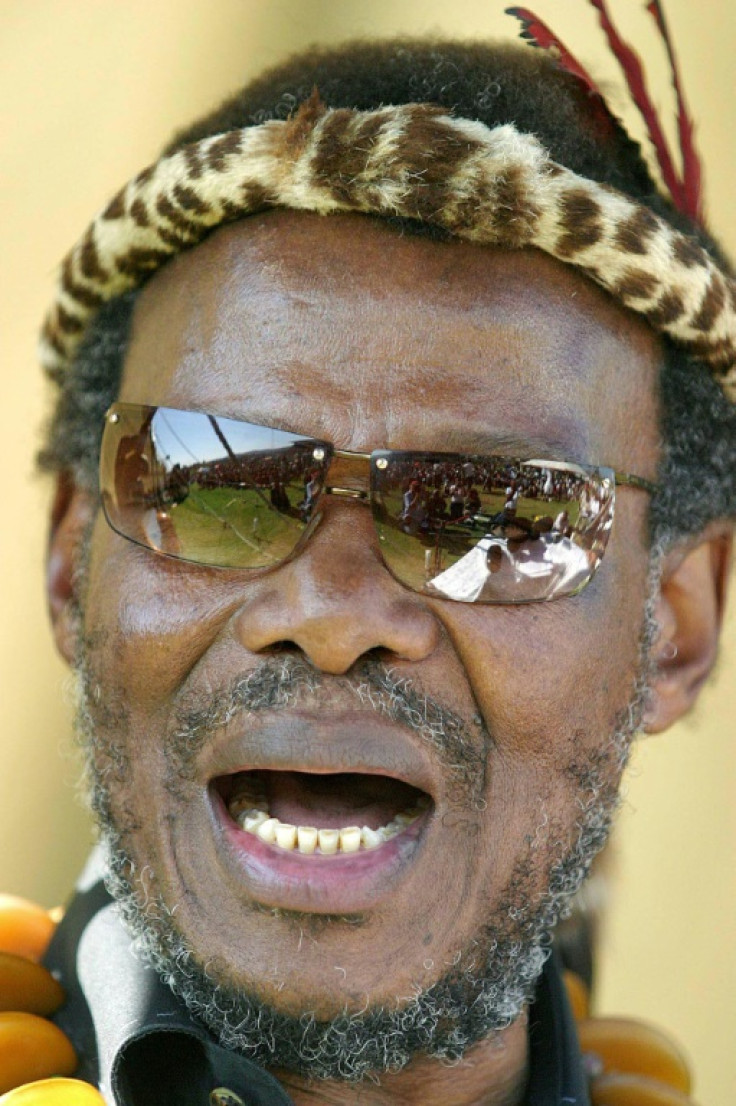

Buthelezi aged with his gutsy demeanour right until his last days, fiercely protecting the Zulu monarchy.

In 2021, in his 90s and playing his role as the traditional premier of the Zulu nation, he actively mediated in the succession squabbles following the death of the Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini.

He sent vicious messages to opposing factions in televised speeches, sparking nostalgia of his once militant leadership style.

But soon after the new king was crowned, reports of a rift with Buthelezi started to emerge, pointing to a waning influence at court.

Debilitated and barely able to walk, the once-feared leader stood hunched back and small, a shadow of his former self, peering at the crowd over his glasses perched on his nose, as he attended the Zulu annual reed dance in September 2022.

His wife Irene died in March 2019.

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP