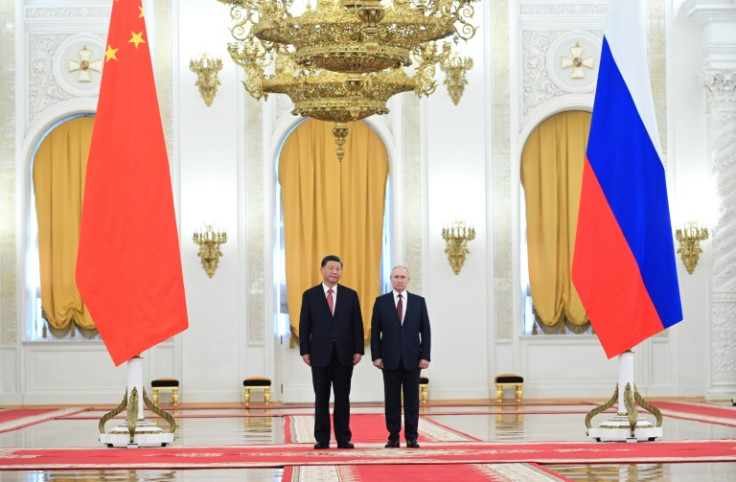

AFP

Xi Jinping’s pomp-filled visit to Moscow underscored a burgeoning but unequal alliance between the two countries, cementing China’s status as a “big brother” to Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

Recently indicted for war crimes, Russia’s KGB spook-turned-president is grateful for any diplomatic support he can get.

So when the Chinese president embarked on a bells-and-whistles three-day visit to Moscow, that was a win in itself.

After all, it is difficult to be painted as an international pariah when hosting one of the world’s most powerful men.

But Putin — bogged down in Ukraine, his economy groaning under the strain of Western sanctions and forecast to shrink by about 2.5 percent this year — needed more than a diplomatic grip and grin.

What happened behind closed doors is difficult to know. But in public, Xi delivered very few of the big-ticket items on Putin’s wish list.

China’s leader pledged a trade lifeline and some moral support, but more conspicuous was that he did not commit to providing arms for Russia’s depleted forces in Ukraine, a move that would have invited Western sanctions on China.

There was also no long-term Chinese commitment to buy vast quantities of Russian gas that is no longer flowing to Europe.

European imports of Russian gas have dropped by about 60-80 billion cubic metres a year, according to the International Energy Agency, leaving a gaping hole in Russia’s finances.

Xi has taken advantage of this, snapping up some of that supply on the cheap.

But he has also shied away from Putin’s request to build a pipeline bringing gas from vast Siberian fields to China, with a non-committal Beijing insisting more study is needed.

Having seen Russia’s ability to pull the plug on Europe, Beijing appears in no hurry to create long-term dependence on Russian gas that the so-called “Power of Siberia 2” pipeline would bring.

That lack of commitment “clearly shows (the) unsentimental and interests-driven nature of China’s ‘friendship’ with Russia,” said Asia Society expert Philipp Ivanov.

As far as Xi is concerned, the visit required few concessions in exchange for achieving important strategic and symbolic goals — presenting a united front against the United States, amplifying Xi’s statesman status, and deepening the perception of Russian dependence on China.

“Xi’s meetings with Putin may have taken place on the Russian president’s home turf, but it was clear as day just exactly who was in charge,” said Brian Whitmore, a Russia expert at the Atlantic Council.

“The body language said it all. In one joint public appearance this week, Xi confidently leaned back in his chair, relaxed, and smiled. Putin in contrast, appeared nervous and anxious as he bent forward and fidgeted.”

Chinese state TV helped burnish Xi’s statesman credentials at home, airing lengthy clips of him being greeted on the airport tarmac by an honour guard and by flag-waving Muscovites along his motorcade’s route.

Xi’s visit appeared to be part of a concerted effort to amplify China’s diplomatic clout.

Recent decades have seen Beijing flex its economic muscle from Asia to Africa, and push its security presence far beyond the Chinese mainland — from a military base in Djibouti to naval facilities in the South China Sea to small-scale security deployments to the Solomon Islands.

Until now, China’s diplomatic power has lagged behind its economic and military power.

But that is starting to change, with China floating a Ukraine peace plan, brokering a detente between arch-rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia, and through Xi’s high-profile visit to Moscow.

According to Whitmore, the visit also took advantage of Putin’s current weak position.

Xi’s trip “illustrated just how dependent on China that Russia has become since being cut off from the global financial system, Western markets, and Western technology,” said Whitmore.

That is a significant role reversal from the Cold War when the Soviet Union was considered China’s “big brother”.

“The Sino-Russian relationship is developing on Beijing’s terms and Putin has no choice but to accept that. He is now Xi’s junior partner,” he said.

But experts are quick to caution that Putin — a wily operator who has survived for decades in the cutthroat world of Kremlin politics — may be dependent, but that does not make him subservient.

“While the relationship is clearly unequal — the Chinese economy is 10 times larger than Russia’s — and Moscow’s dependency on China is rapidly growing, it’s too early to call Russia a vassal state,” said Ivanov.

AFP