AFP

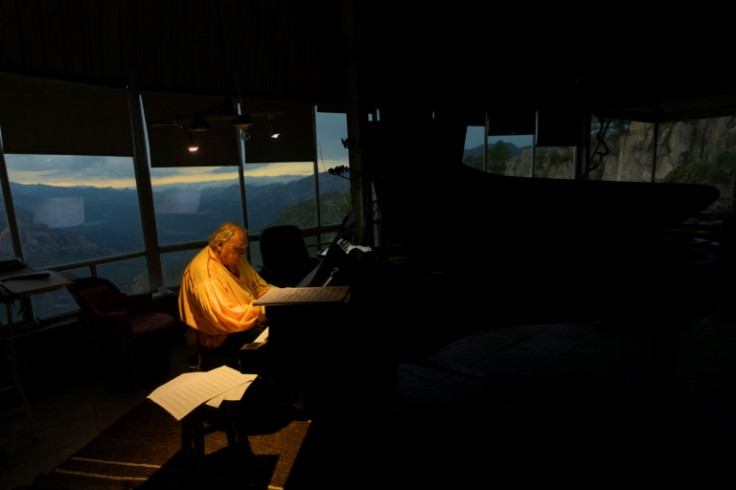

Romayne Wheeler sits at his grand piano overlooking Mexico’s Copper Canyon and plays music inspired by the mountains and remote Indigenous communities that he now dedicates his life to helping.

The 81-year-old California-born composer no longer lives in the cave where he slept with his solar-powered portable piano after arriving several decades ago in the Sierra Tarahumara in northwestern Mexico.

But he feels as close as ever to the nature and Indigenous Raramuri people who welcomed him into their lives, sharing their food, music and culture.

“I feel truly that all of this area around me is my studio,” Wheeler told AFP in his stone house perched on the canyon’s edge, several hours from the nearest significant town along winding mountain tracks.

“Every tree, every plant, every flower — everything here has something to tell me,” he said.

Wheeler’s love affair with the Sierra Tarahumara began in 1980 when he was in the United States studying Indigenous music and a snowstorm made it impossible to travel to a Native American reservation near the Grand Canyon.

Leafing through a copy of National Geographic magazine, he came across pictures of the remote Mexican region and decided to see it for himself.

“It was like coming home,” he recalled, wearing the Indigenous-style shirt and traditional sandals that he now prefers to Western attire.

“The people that are most revered here are the musicians. They stand in high honor like the shamans,” he said.

The mountainous corner of Chihuahua state is part of the notorious “Golden Triangle,” a region with a history of marijuana and opium poppy production as well as drug cartel violence.

Wheeler identified so much with the philosophy of the Raramuri — also known as Tarahumara — that he came back for several weeks each year before settling there permanently in 1992.

They were “people who shared everything they had, who considered the person that is of most value is the one that helps others the most, and contributed something positive to humanity,” he said.

When he first arrived, the Raramuri — whose name means “light-footed ones” and who are renowned for their running stamina — showed Wheeler a small cave where he could practice and keep his electric piano dry.

“My friends said sometimes with the wind just right they could hear my little tiny instrument all the way across the canyon,” he remembered.

One young child, a neighbor’s son, showed particular interest, so Wheeler taught him to play and sent him to study in the Chihuahua state capital.

Now Romeyno Gutierrez, his protege, is an acclaimed pianist in his own right who performs abroad and accompanied Wheeler on two tours of Europe.

“He’s the first pianist and composer of Indian heritage that I know of on our continent,” Wheeler said proudly.

Bringing his 1917 Steinway grand piano to the village of Retosachi was almost as much of an odyssey as Wheeler’s own.

The dream to put a piano on a mountaintop was born in Austria where Wheeler, a keen mountaineer, studied and lived for 32 years, but where harsh winters made it impossible.

In Mexico, he hired a professional moving company to bring the fragile musical instrument from the western city of Guadalajara as far as it could into the mountains.

It then took 28 hours to reach Wheeler’s home by truck along dirt mountain roads with the piano laid on its side, supported by piles of potatoes, he said.

“We went at a walking rhythm for most of the way because of all the potholes,” he added.

Despite the remoteness of his home, affectionately named Eagle’s Nest, visits from his neighbors and the company of his dogs mean that Wheeler never feels alone.

“I feel more lonely in the city because of all the people around that have nothing to say to each other,” he said.

He has 42 godsons in the area, one of the poorest in Mexico, where limited access to clean water, sufficient food and healthcare pose major challenges to communities that rely mostly on subsistence agriculture.

In the early 1990s, Wheeler decided to use proceeds from the concerts he performs around the world to establish a school, a clinic and a scholarship program.

“They’re very good people. They help a lot,” said one of his neighbors, Gerardo Gutierrez, who was a child when he first met Wheeler.

“They gave away blankets when it was very cold. And sometimes they got groceries for the people here,” the 49-year-old added.

Giving back to the community has also given Wheeler a deeper sense of purpose.

“These years have been the most happy years of my life really because I feel like my music is doing something of value to help humanity,” he said.

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP

![Harrowing Video Captures Moment Giant Crocodile Kills Costa Rican Footballer and Carries His Body in Its Jaws as Onlookers Watch in Shock [GRAPHIC] Harrowing Video Captures Moment Giant Crocodile Kills Costa Rican Footballer and Carries His Body in Its Jaws as Onlookers Watch in Shock [GRAPHIC]](https://data.ibtimes.sg/en/full/69189/crocodile-kills-footballer.jpg)