One night in September 2020, Hanna Kanavalava fled her native Belarus and crossed the border into Ukraine — on foot, in the dark and with her two young grandchildren in tow.

“That’s when Ivan asked me, ‘Grandma, is Mum in prison?’ And that’s when I told him the truth,” Hanna said.

Ivan, now nine, and his sister Anastasiya, seven, have lived in exile for almost four years, separated from both their parents, who were jailed in Belarus for opposing the strongman President Alexander Lukashenko.

They are just two among hundreds of children forced apart from their parents by Lukashenko’s crackdown on dissent, a campaign that has jailed hundreds of regime critics following 2020 protests that threatened his quarter-century grip on power.

Ivan and Anastasiya’s mother, Antanina Kanavalava, worked for Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, the opposition leader who claimed victory against Lukashenko in presidential elections that summer.

Rights groups and independent monitors say the vote was marred by rampant fraud and ballot stuffing as official results showed Lukashenko, in power since 1994, won with 80 percent.

His riot police responded forcefully against the protestors and a wave of arrests and tightening repression followed.

Antanina was arrested in September 2020 and sentenced to five and a half years in prison, while the children’s father, Siarhei Yarashevich, was given two sentences totalling six years and three months.

The outlawed Viasna human rights group estimates Belarus has 1,400 political prisoners.

Hanna Kanavalava, 60, whisked the children out of the country just four days after their mother was arrested.

She took them briefly to Ukraine, and then to Poland, which has become a shelter for many of the hundreds of thousands that have fled.

Hanna feared Belarusian authorities would take custody of Ivan and Anastasiya if they stayed, potentially using them to pressure their parents.

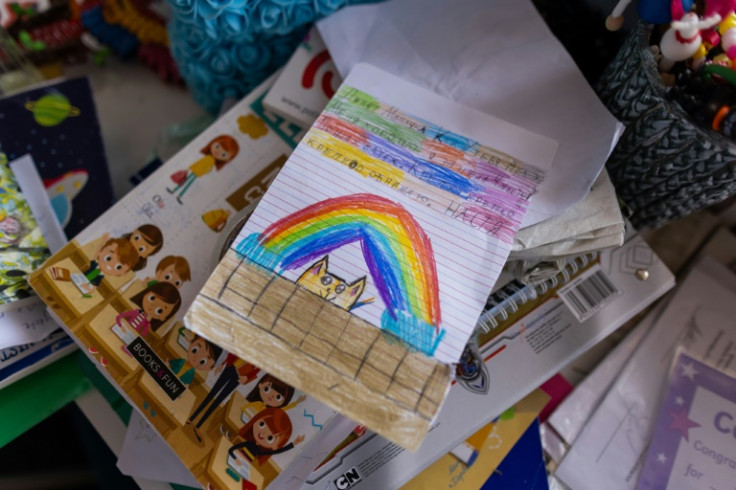

The children write their parents letters, though correspondence with political prisoners, when permitted, is heavily restricted and censored.

Anastasiya read out parts of one of them for an AFP reporter: “Hi Mum, how are you? I’m doing fine. I came fourth in the chess tournament. A big, big, big hug.”

The children are allowed a maximum five-minute video call once a month with their mum, under the supervision of prison guards.

Hanna worries that her grandchildren, especially the younger Anastasiya, are starting to forget their parents.

But Anastasiya — who says she wants to become a “doctor or veterinary surgeon… to earn lots of money” — said she wanted to help.

“I want to spend all this money to look after mum and dad. And to buy them a ticket to Warsaw when they are released,” she said.

Her mother, Antanina, has developed serious eyesight problems in jail.

She is set for release next year — if the sentence is not increased.

Then, “my mission will be to help her to be reborn, to look after herself… and to reconnect with her children,” Hanna said, whispering so the children could not hear.

Experts fear the emotional and psychological damage the situation inflicts on the children of those behind bars.

Volha Vialichka, a psychologist from Belarus, told AFP she has met 60 children of political prisoners and sees a lot of “pain, despair and anger”.

Many resemble “premature adults”, she said.

“They are very sensitive to moments that remind them of their circumstances, when they say to themselves, ‘I am alone, without mum and dad.'”

While safe from repression in Poland, Hanna and the children still face instability.

They have no stable accommodation due to a lack of income, and rely on support from the Belarusian and Ukrainian diaspora, as well as the Polish state.

For Ivan, a recent move to a new apartment on the outskirts of Warsaw reawakened the trauma of their escape from Belarus.

He has nightmares of “his parents being taken away by soldiers” and a “wolf in a forest”, Hanna said.

She regularly takes the children to demonstrations organised by Belarus’s opposition in exile.

Since May 2023, Hanna has also been responsible for two other children — Marcel and Timur Zhuravlyov, brothers aged five and 15.

Their mother, Olga Zhuravlyova, another Belarusian political opponent who fled to Poland, died last April after falling into depression and suffering a drug overdose.

“My mum died because there was nobody there for her,” Timur said.

Marcel, who was playing football in a Spiderman cap when AFP visited the group, cried a lot when he realised his mother had gone, his brother said. Now he doesn’t talk about it.

Hanna said Timur looked like a “scared kitten” at first, but his confidence has grown.

Their experience has forced the children to become “more solid”, she said.

“You have to form a team and be strong,” she said, before adding: “Nobody will ever replace their mum.”

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP