Senegalese news organisations widely heeded a call Tuesday for a news blackout to protest against economic measures by the new government which they say threaten the industry.

Most newspapers did not publish and two popular private radio stations played music instead of broadcasting the news.

Private television stations such as TFM, ITV and 7 TV demonstrated solidarity with the protest by displaying its slogan and image — three raised fists gripping a pencil.

The Senegalese Council of Press Distributors and Publishers (CDEPS) said in a joint editorial published on Monday that the freedom of the press was “threatened in Senegal”.

The body, which groups editors of private and public companies, complained that the authorities, who came to power in April, were “freezing the bank accounts” of media companies for non-payment of tax.

It also condemned the “seizure of production equipment”, the “unilateral and illegal termination of advertising contracts” and the “freezing of payments” due to the media.

“The aim is none other than to control information and tame media professionals,” the CDEPS said.

Le Soleil was among several pro-government newspapers that did not follow the “Day Without Press” action.

Earlier, journalists from the RFM private radio station met to discuss the blackout.

News director Babacar Fall said the new government’s campaign to clamp down on the non-payment of tax was a means of exerting pressure on private media “to extinguish critical voices”.

“Tax pressure is turning into tax harassment… We are being asked to pay tax when we don’t even have enough money to pay salaries,” he added.

Ana Rocha, a journalist at the meeting, expressed hope the blackout would spur the government to come to the negotiating table.

“It’s a question of survival,” Rocha said, noting that several of her colleagues have been made redundant.

At a newspaper kiosk in the centre of the capital Dakar, Homere Badiane said he empathised with the organisers of the protest.

“When you feel you’ve been wronged, it’s normal to defend your interests,” the 70-year-old said.

By contrast, Ousmane Balde, 38, came especially to buy the only three newspapers that hit the shelves in “solidarity”.

“In (former president) Macky Sall’s time, when the police gassed or imprisoned certain journalists, nobody said a word,” he said.

“Today, there’s a backlash as we’re asking them to pay tax and they’re taking offence at this.”

Senegal’s media sector has long faced economic difficulties and many reporters complain of precarious working conditions.

Last month, the company behind two of the most widely read sports dailies suspended publication after more than 20 years due to economic difficulties.

At the same time, the country is experiencing “a crisis of public trust in the media”, according to global watchdog Reporters Without Borders (RSF), urging an end to the “tug-of-war” between the new government and private media.

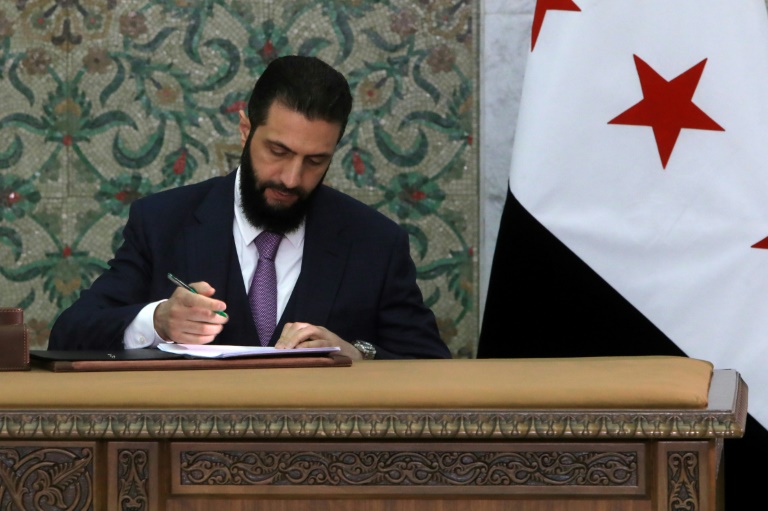

In late June, recently installed Prime Minister Ousmane Sonko denounced what he called the “misappropriation of public funds” in the sector, alleging some media chiefs were failing to pay social security contributions.

“We are no longer going to allow the media to write whatever they want about individuals, in the name of the so-called freedom of the press, without having any reliable sources”, he also declared on June 9.

His comments were taken by many in the profession as a threat.

From 2021 to 2024, Senegal slipped from 49th to 94th place on the RSF world press freedom index.

The rights group recently urged Senegal’s new president to take action to promote press freedom after three years of arrests and violence against journalists.