As Edinah Nyasuguta Omwenga fought for her life after developing complications during childbirth, she overheard doctors in the Kenyan hospital describe her condition as a textbook example of the damaging — even deadly — effects of genital mutilation.

But unlike thousands of girls across East Africa, Omwenga underwent female genital mutilation (FGM) in a hospital, at the hands of a health worker — part of a worrying trend keeping the illegal practice alive.

“I was seven years old… no one told me it would cause so many problems,” Omwenga, now 35, recalled.

When Kenya banned FGM in 2011, few expected that the practice — traditionally performed in public with pomp and ceremony — would migrate to backroom clinics and private homes, with nurses and pharmacists doing the procedure underground.

Medicalised FGM — as it is known — is defended by practitioners and communities alike as a “safe” way to preserve the custom, despite risks to the victim’s physical, psychological and sexual health.

According to a 2021 report by UNICEF, medicalised FGM is growing in Egypt, Sudan, Guinea and Kenya, where it threatens to undo progress made by the East African nation in stamping out the tradition, which involves the partial or total removal of the clitoris.

Kenya estimates that FGM rates fell by more than half “from 38 percent in 1998 to 15 percent in 2022”. However, campaigners caution that actual figures are likely to be higher.

In Kisii county, 300 kilometres (180 miles) west of Nairobi, more than 80 percent of FGM procedures are carried out by health workers, according to government data.

Doris Kemunto Onsomu spent years administering the cut to schoolgirls in the hilly region, believing it was a significantly safer alternative to the traditional procedure she underwent as an adolescent.

“Because I was aware of the risk of infection, I would use a fresh blade every time,” she told AFP.

“I thought I was helping the community.”

The lucrative gig added 50 percent to her monthly income as a health worker before she stopped the practice.

Demand came from all quarters, including upper middle-class households.

“Traditions defy education. It takes a long time to unlearn certain practices,” the 67-year-old said.

Tina — not her real name — the daughter of an engineer, was at her grandmother’s house in Kisii when a health worker turned up late at night to perform the procedure on the eight-year-old and her cousin.

“It felt like the world was ending, it was very painful,” she told AFP, recounting her confinement on the orders of her grandmother, who told her she had to remain in seclusion until the wound was healed.

Now a student at the University of Nairobi, the 20-year-old campaigns against the practice, reflecting a growing push by FGM survivors to eradicate the custom.

As the youngest of five sisters raised in Kisii, Rosemary Osano said she “felt pressure” to go along with tradition when she was cut.

“People feel like we have adopted Western culture in so many ways… so they want to hold on to this (practice) as a way of holding on to their culture,” the 31-year-old graduate told AFP.

The belief also persists across the diaspora, with families flouting local laws and travelling to Kenya for the procedure.

In October this year, a London court convicted a British woman for taking a three-year-old girl to a Kenyan clinic to undergo medicalised FGM.

“They say that without this (cut) the girl will be a harlot,” she added.

President William Ruto has urged Kenyans to stop practising FGM, but Nyaramba said the authorities needed to take tougher action against perpetrators, including health workers and victims’ families.

“If you (throw) a parent… in jail and highlight it, then people will fear it.”

But other campaigners caution that a crackdown could drive the practice even further underground.

Instead, organisations have chosen to focus on building awareness and persuading families to opt for alternative rites of passage, combining celebratory coming-of-age rituals with traditional teachings.

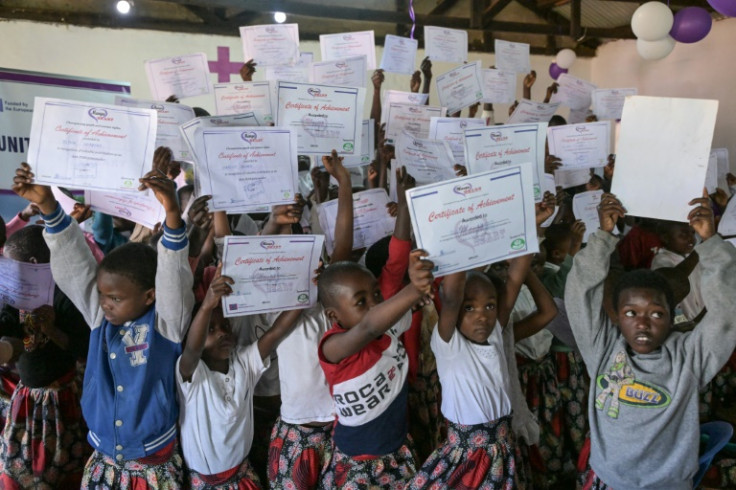

At a recent ceremony organised by Kenyan non-profit Manga HEART in Kisii, around 100 girls — wearing kitenge skirts and aged between seven and 11 years old — sang songs and recited rhymes, urging their parents to “save me from FGM”.

As the children received “certificates of achievement”, their beaming relatives applauded and ululated — the public ceremony reflecting an emerging resolve to end the dangerous practice.

Some of the grandmothers and mothers celebrating that day knew the stakes all too well.

“I lost a lot of blood during FGM… but I couldn’t stop it from happening,” said Omwenga, the mother-of-three who nearly died during childbirth.

“I am here today because my girl is not going to go through FGM,” she said.

“I don’t want my daughters to suffer like me.”

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP