AFP

Poring over family photographs, Jessica Watt Dougherty voices anguish over her father’s death — which she attributes to misinformation on an online platform, an issue at the heart of a knotty US debate over tech regulation.

The US Supreme Court will this week hear high-stakes cases that will determine the fate of Section 230, a decades-old legal provision that shields platforms from lawsuits over content posted by their users.

The cases, which are among several legal battles nationwide to regulate internet content, could hobble platforms and significantly reset the doctrines governing online speech if they are stripped of their legal immunity.

“I watched my father die over the screen of my phone,” Dougherty, an Ohio-based school counselor, told AFP.

Her father, 64-year-old Randy Watt, refused to get vaccinated and died alone in a hospital last year after struggling with Covid-19.

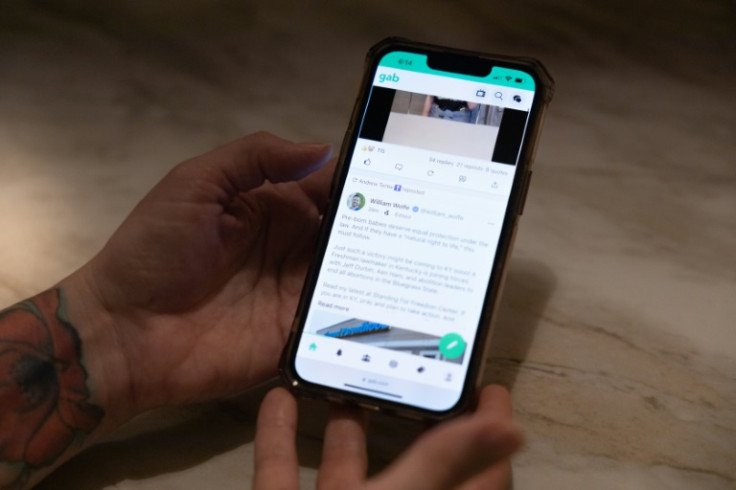

After his death, his family discovered that he had a secret virtual life on Gab, a far-right platform that observers call a petri dish of misinformation and conspiracy theories.

To his vaccinated family members, his Gab activities explained why he chose not to get inoculated against Covid-19, a decision that ultimately had fatal consequences.

The influence of vaccine misinformation on Gab was also apparent after Watt drove himself to the hospital and started what his family called an “illness log,” documenting to his followers how he treated himself for the coronavirus.

He wrote that he was on drugs such as ivermectin, which US health regulators say is ineffective, and in some instances dangerous, to use as a treatment for Covid-19. Gab, which has millions of followers, is rife with posts promoting ivermectin.

“I feel very, very strongly that the content (on Gab) is careless and disrespectful, racist and scary,” Dougherty said.

“My dad spent a lot of time virtually surrounded by people with ideas about the pandemic being a hoax, Covid being fake, the vaccine being unsafe, the vaccine being deadly… Those are the belief systems (he) took on.”

Such assertions that platforms are responsible for false or harmful user content are at the core of the Supreme Court cases.

The most closely watched case will be heard on Tuesday. A grieving family asserts that Google-owned YouTube is liable for the death of a US citizen in the 2015 attacks in Paris claimed by the Islamic State (IS) group.

Her relatives blame YouTube for having recommended videos from the jihadists to users, helping cause the violence.

And on Wednesday, the same justices will consider a similar case involving the victim of an IS attack at a nightclub in Turkey, but this time asking if platforms should be subject to anti-terrorism laws, despite their legal immunity.

The court’s ruling is expected by June 30.

Lobbyists for the platforms fear a flood of lawsuits if the court rules in favor of the victims’ families, a decision that could have a game-changing ripple effect on the internet.

Platforms are “not going to get every single call right,” Matt Schruers, president of the Computer & Communications Industry Association, which represents the biggest US tech companies.

“If courts penalize companies that miss needles in haystacks, that sends a signal, ‘don’t look at all,’ and that turns the internet into a cesspool of dangerous content,” he told AFP.

Or, Schruers added, it could prompt the world’s biggest platforms to over-filter, seriously limiting the flow of free speech online.

But a change could offer Watt’s relatives an avenue to seek justice from Gab, whose founder Andrew Torba has previously urged the US government to keep Section 230 “exactly the way it is.”

“We seek to protect free speech on the internet,” Torba wrote to former president Donald Trump in an open letter in 2020.

“Section 230 is the only thing that stands between us and an avalanche of lawsuits from activist groups and foreign governments who don’t like what our millions of users and readers have to say.”

Founded in 2016, Gab has become a haven for white supremacists and conspiracy theories targeting Jews, LGBTQ people and minorities, the Stanford Internet Observatory wrote in a report.

Even among misinformation-ridden fringe platforms, Gab stands out for its blanket refusal to “remove the most extreme racist, violent, and bigoted content,” the report said.

Dougherty noticed the same when she created an account on Gab after her father’s death.

“You can’t scream fire in a crowded theatre,” she said.

“We can’t speak things that are going to harm other people. There’s a lot of people screaming fire in a crowded theatre on Gab.”

AFP

AFP

AFP

AFP