KEY POINTS

- The cirrate octopus Cirroteuthis muelleri is often found in the Arctic Ocean

- Prior studies of the octopuses’ stomach contents suggested that they feed on the seafloor

- Researchers observed a handful of octopuses descending into the bottom of the ocean to seemingly hunt

The mysterious octagons found at the bottom of the Fram Strait in the oceanic passage between Greenland and Svalbard were likely the creation of a deep-sea species of octopus, a recent study has found.

Scientists said they found during a research cruise 106 octagons, whose sizes range from as small as Oreos to as big as extra-large pizzas, across the muddy Fram Strait seafloor, as deep as 14,000 feet below the surface.

Researchers suggested that the cirrate octopus Cirroteuthis muelleri plunges to the deep seafloor to feed and leaves behind orderly and geometric octagonal imprints in the silt, according to a paper published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

One of the two main types of octopuses, cirrate octopuses live in the deep seas all over the world. They are described as inkless and gelatinous and have a large pair of lop-eared fins on their heads, which earned some species the nickname “dumbo” octopus, according to a report by the Defector.

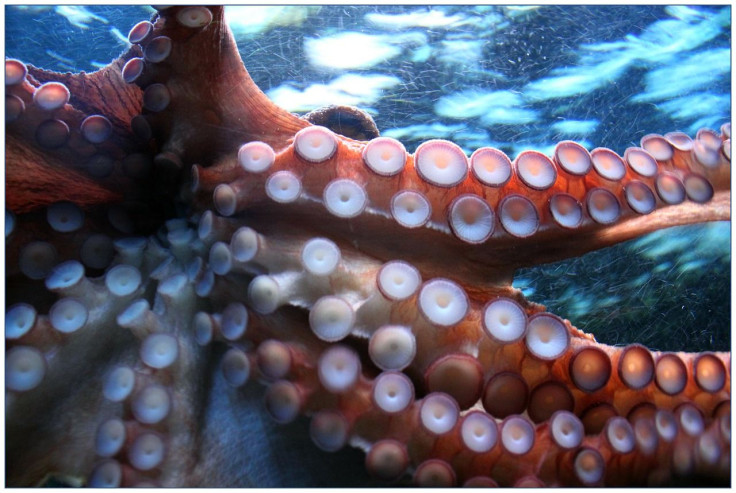

“Their most distinct external characteristics are a semi-gelatinous body consistency, a well-developed web and paired, finger-like projections called cirri that are situated in between suckers,” the researchers wrote in their study.

C. muelleri octopuses are found in the Arctic Ocean and are often seen motionless and smoothly drifting whenever observed in the open water at less than 2,000 feet from the surface.

However, prior studies of C. muelleri octopuses’ stomach contents found bottom-dwelling prey like crustaceans, which suggested that they fed on the seafloor, according to the study.

The authors of the study, through recent deep-sea surveys in the Arctic, observed a handful of octopuses descending to the bottom of the ocean to seemingly hunt.

The octopuses all repeated the same movements. They initially swam slowly just above the seafloor with their arms curved to be parallel with the ground. They then spread their arms out and enveloped the ground below them. They rotated their fins to suck out whatever prey they might have found, and in the process, created octagon shapes on the ground.

Afterward, they returned back to the open water.

“The utilization of the water column for drifting and the deep seafloor for feeding is a novel migration behavior for cephalopods, but known from gelatinous fishes and holothurians,” the researchers wrote.

“Drifting in the water column may be an energetically efficient way of transportation while simultaneously avoiding seafloor-associated predators,” they continued.

Although scientists are still learning about deep-sea environments, it was interesting for them to discover that some creatures, whether to avoid predators or save energy, drift on ocean currents, which C. muelleri octopuses also do with another layer of style and art.